Pass this on to someone else! If you can, make copies! Appearing since 1972

This issue is dedicated to FATHER SIGITAS TAMKEVlČlUS, member of the Catholic Committee for the Defense of Believers' Rights, who by his life has demonstrated the most beautiful love for God and Country.

CHRONICLE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN LITHUANIA, No. 58

In this issue:

1. The Trial of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas 4

3. The Friends of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas Speak 18

5. Jadvyga Bieliauskienė Sets Out Again on the Gulag Road 25

6. Raids and Investigations 26

11. The Church in the Soviet Republics 49

Lithuania May 22, 1983

On May 3, 1983, the Supreme Court of the LSSR took up the case of the Pastor of Viduklė, member of the Catholic Committee for the Defense of Believers' Rights, Alfonsas Svarinskas. News of the trial quickly spread throughout Lithuania. Many doubted the report, since even his relatives knew nothing of the up-coming "public"trial.

Nevertheless, upon arrival in Vilnius, May 3, the doubts were dissipated. The neighborhood of the Lenino prospektas was surrounded by militiamen and soldiers in militia uniforms, while access to the Supreme Court, across from the Library of the Republic, was completely out of the question. Agents in uniform and mufti admitted into the courtroom only those with special invitations, while the friends and acquaintances of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas, who had gathered from all corners of Lithuania, were rudely chased by militiamen into Lenino prospektas at the Library of the Republic trolley bus stop.

It was difficult even for relatives to get into the courtroom. At 9:00 AM, when (Mrs.) Janina Pupkienė the sister of Father Svarinskas, arrived at the courthouse, KGB agents tried to convince her that there was no reason to attend the trial. When she would not give up, they told her to come at 10:00 AM; and when she arrived at the appointed time, they told her that she was too late, and admitted her into the courtroom only after the lunch break.

At 9:30 AM, the brother of the priest on trial, Vytautas Svarinskas, showed up at the courthouse with several priests; the latter were finally successful in obtaining permission for the brother to enter the courtroom. Vytautas Svarinskas said that on account of his advanced, age, he would get lost in town, and so he wished that his daughter would be allowed into the courtroom with him, but this request was categorically denied.

The priests were unable to get into the courtroom; officials explained that there was no room, even though the courtroom was half empty — there were about sixty people, and two rows of benches had been pushed fogether. Father Sigitas Tamkevičius was told by the KGB, "You are being summoned as a witness; bring your summons from Kybartai, and tomorrow you will be able to take part."

Thus, except for a brother and sister, not a single priest or lay person was allowed in. Even before the trial began, on the street

Father Alfonsas Svarinskas

leading to the courthouse, a round-up of people began. Agents tried to force Father Svarinskas' housekeeper, (Miss) Monika Gavė-naitė, into a militia car; it seems she had expressed a desire to get into the courtroom. (Miss) Regina Teresiūtė, a resident of Kelmė, who tried to defend the housekeeper, was forced into a car by four militiamen, who said that they had been waiting for her a long time, and took her to the Rayon of Lenin Militia Department, where they sentenced her to ten days for alleged hooliganism.

After taking Father Alfonsas Svarinskas into custody, government atheists began a smear campaign against the arrested priest, the Catholic Committee for the Defense of Believers' Rights and the most zealous priests, in an effort to set everyone against them. However, in spite of the shrill propaganda, throughout Lithuania, a campaign of collecting signatures began for Father Svarinskas' release. The greatest work in this regard was performed by the youth, which risked having its way blocked to higher studies, losing jobs, or being expelled from institutions of learning.

The KGB did everything it could to intimidate those collecting signatures: In one place they would ridicule them in front of church, in another, the chekists would take away the signatures (the Church of Griškabūdis) or priests (Father Nikodemas Čėsna of the Church of the Resurrection in Kaunas) would expell them from the churches, etc.

In the larger centers, KGB agents, noting the more active collectors of signatures, summoned them to KGB Headquarters for blackmail, e.g., in Kaunas:

Arūnas Rekašius — taken from work to the Army Commissariat Saulius Kelpšas — taken to the KGB from home Antanas Žilinskas — taken from work to the KGB for interrogation

Arūnas Rekašius and Jaunius Kelpšas were seized while collecting signatures in front of church in Nedingė (Rayon of Varėna).

Saulius Kelpšas, Valdas Kelpšas and Kęstas Rekašius were detained in Varėna for "identity checks".

Along with the painful events, there were happy incidents, also, when many people would sign with great enthusiasm, even with tears in their eyes. There were some who volunteered, if necessary,

Father Vincas Vėlavičius (left) and Father Alfonsas Svarinskas (right) meet with Petras Paulaitis following his release from thirty-five years in labor camp, November, 1982.

to sign in their own blood on behalf of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas (in Alytus).

At various intervals between 1958 and 1962, I had occasion to be with Father Alfonsas Svarinskas in Mordovia, in Camp No. 7, where over two hundred Lithuanians were confined. Along with Father Svarinskas, there were other priests in camp.

Father Svarinskas was distinguished from the others by his boundless energy, his industry and natural optimism. Organizing holy days or just celebrations with public prayer were pure pleasure for him. Activity was his lifestyle. He was not inclined to philosophical or theological discussions, but if someone engaged him, he would not refuse to debate also. He liked to be with people, and he would quickly note and long remember their good qualities. Father Svarinskas loved external beauty and order, and was especially pained by disorder in spiritual life.

He was constantly preoccupied with questions of the nation's spiritual life, and was especially pained by the obsequiousness of some high-ranking clergy toward the atheistic government. Father Svarinskas respected and admired the martyr-bishops, and was deeply affected by news of Bishop Ramanauskas' death, saying that it was a great loss for the entire Lithuanian nation.

On May 6, 1983, in Vilnius, in the course of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas' trial, a criminal case was started against Father Sigitas Tamkevičius, on the basis of the LSSR Criminal Code Par. 68. Id. He was arrested right in the courtroom, and confined in the KGB isolation prison.

Even before his arrest, on May 4, when Father Tamkevičius was summoned to the LSSR Supreme Court in Vilnius as a witness in the case of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas, large numbers of KGB and militia arrived in Kybartai. At about 1:00 PM, militia officials, coming to the rectory, demanded to see Father Jonas Boruta, but he was no* home at the time. All three days, up till the arrest of the pastor, Kybartai was zealously guarded by local agents of the KGB and militia, along with those who had come in from elsewhere.

Saturday, May 7, militia officia, A. Kazlauskas came to the rectory and asked again for Father Boruta. Not finding him, he warned once more that if Father Boruta said Mass on Sunday in the Church in Kybartai, he would meet the same fate as Father Tamkevičius.

Sunday, May 8, the church in Kybartai could hardly contain the faithful gathered for services. During the 10:00 AM Mass, the Dean of Vilkaviškis, Father J. Preikšą, spoke directly to the aching hearts of the faithful: "I know that today your pain is so great that any

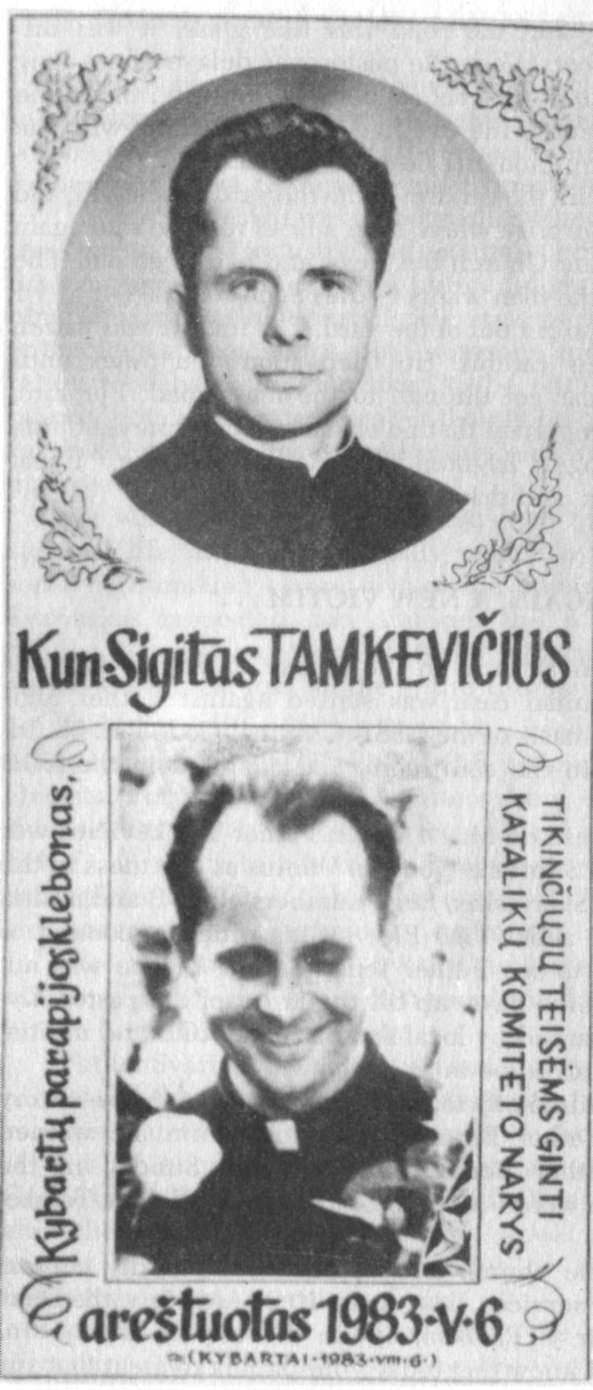

A card being circulated in Lithuania following the arrest of Father Sigitas Tamkevičius. "Father  Sigitas Tamkevičius, Pastor of the parish of Kybartai, member of the Catholic Committee for the Defense of Believers' Rights. Arrested May 6, 1983. Kybartai, August 6, 1983."

Sigitas Tamkevičius, Pastor of the parish of Kybartai, member of the Catholic Committee for the Defense of Believers' Rights. Arrested May 6, 1983. Kybartai, August 6, 1983."

words of comfort would ring hollow; however, keep always before your eyes the event described in Holy Scripture when the prayers of the faithful reached heaven and an angel freed their beloved teacher, the Apostle, Saint Peter from prison. So you are powerless today, but at the same time strong, because on your side you have God, you have prayer. Our greatest weapon is prayer," said Father Preikša, or words to that effect.

May 16-18, 1983, in the Supreme Court at Vilnius, the trial of (Mrs.) Jadvyga Bieliauskienė (arrested November 29) took place.

As is usual, only her nearest relatives could get into the courtroom: her sister, her grown son and her husband. In front of the Supreme Court, and on Lenino prospektas, there was an atmosphere of seige: Militia stood at every trolley bus stop, and more of them were on the trolley buses, so that not a single person would think of making a move toward the court house.

Those arriving gathered at the Gates of Dawn (Trans. Note — A venerable Marian Shrine), and prayed throughout every day. The accused, Jadvyga Bieliauskienė, even though she had languished for many months in the KGB cellars, was not the least bit morally broken: She was erect, smiling, firm and outspoken. At the trial, (Mrs.) Bieliauskienė refused the services of an attorney.

The prosecutor accused her of anti-Soviet activities: organizing children in church, and duplication and dissemination of anti-Soviet literature.

Viduklė.

On May 13, 1983, a search was carried out at the Viduklė rectory, in the quarters of Father Svarinskas' housekeeper, (Miss) Monika Gavėnaitė. In charge of the search was Senior Lieutenant T. Vaivada, an inspector from the criminal investigation section of the Raseiniai Rayon.

During the search, the following were seized:

The youth publication, Lietuvos ateitis (The Future of Lithuania, No. 5;

Tikybos pirmamokslis (A Primer of Religion) (150 copies); Aušros žvaigždė (The Day Star) (48 copies); 138 photographs of former prisoners and exiles; 72 photographs of a religious nature,

60 pages of various texts written on several typewriters, Three notebooks with addresses, Six audio tapes. Books:

Jaunoms širdims (To Young Hearts); Trupinėliai (Crumbs);

The search lasted more than two hours. That very day, a search was made at the home of (Miss) Gavėnaitė's father, living in Ukmergė Rayon, the Village of Jakutiškiai and at the home of a brother, Julius Gavėnas, living in Kaunas at Kapsų 43-3. At the father's home, they found two photographs of Svarinskas and a petition to the bishops.

Viktoras Petkus writes:

"On August 23, the sum of the years I have spent in prison will be a round and solid twenty. In the twenty years I have spent in houses of detention, I have never seen a fellow countryman who did not celebrate Christmas or Easter. Of course, at Christmas, we had no tree, but on the table we had a beautifully ornamented tree clipped from Horticulture magazine. I made slizikai from cut-up dried bagels, and there was a white plotkelė (Trans. Note — staples of the traditional Lithuanian Christmas Eve supper.) That way, everything seemed to be right. . . but for the first time, I don't know when Lent begins, or Easter occurs.

"Our life is monotonous. For us, receiving newspapers and and magazines is problematical. They claim that periodical literature reaches us three times a week. So they say; but in reality, weeks have gone by without our receiving a single newspaper. If they do deliver the newspapers, they usually bring the magazines only once a week, so that they make an armful. The rule here is that an individual prisoner can keep only five items in his cell, no matter whether books, brochures or magazines; everything else has to be checked with the store room, on the pretext that you can claim it when you want it.

"Theoretically, it looks like a pretty good system. In practice, it

This photograph, taken outside the court in Vilnius on the last day of Viktoras Petkus' trial in 1978, shows, first from left: Antanas Terleckas (currently in exile in Magadan), and third from right: Father Sigitas TamkevicUus, awaiting trial in Vilnius.

sometimes takes over a week to get them to take you to the store room. So you end up in a vicious circle. It's worse with books. Receiving any books from home is categorically forbidden. Book sellers are uninterested in sending us books on order, since they are often returned to the sender; that is, to the bookseller. Thus, in their eyes we become less than serious customers.

The Resurrection bells had just pealed joyfully, and through the streets of the old city, the hymns of the Easter procession re-echoed. A crowd of people flowed into the Kaunas Basilica to greet the Risen Christ. The church was packed to the rafters, the churchyard full. And the automobiles! All the side streets in the area were packed with them! The town square was also covered with a mosaic of cars.

All around reigned a spirit of recollection and solemn peace.

The main altar of the Kaunas Cathedral.

In the cathedral, the services were drawing to a close; when in the city square, among the ant-heap of automobiles, appeared a lone passerby. He walked about in a suspicious manner, as though preparing (and this is how it seemed to some) to cheat or rob someone. However, he did not do so, even though strangely enough, he was constantly writing down something. Soon, one or two automobile owners appeared, who became concerned about the peculiar behavior of the stranger.

Šiauliai

On March 30, 1983, in the Šiauliai Rayon Executive Committee auditorium, a seminar was held for members of Committees of Twenty from religious associations. The seminar was conducted by Assistant Religious Affairs Commissioner P. Raslanas. He tried to say that in Lithuania there is complete freedom of religion, and that more religious literature is published each year. The only bad thing, according to him, is that some priests, under cover of religion, are vilifying the Soviet system. Raslanas called Father Alfonsas Svarinskas the worst offender, and cited excerpts from his sermons.

He was annoyed that outside the churches, signatures were being collected on behalf of Father Svarinskas. The Assistant Commissioner for Religious Affairs named a list of— in his opinion — bad, extremist-oriented priests: Ričardas Černiauskas, Juozas Kauneckas, Sigitas Tamkevičius and others. Raslanas tried to convince everyone that even the Second Vatican Council indicated that the civil government must take suitable measures against those priests who disobey it. Hence, in his words, it is not surprising that they have brought Father Alfonsas Svarinskas to trial.

After the lecture, there were questions:

"And where can the religious literature you have published be obtained? True, we have seen on television the covers of the literature you mentioned, however, that's where it all ends. A large part of that literature has ended up in the West for propaganda. Another part was taken by the atheists, and for us faithful, there were only crumbs left."

Raslanas held up two prayerbooks, and tried to make excuses, "I only took two. Ask Father Aliulis for religious literature."

Lazdijai

On March 1, 1983, seventy-six representatives of the youth of Lazdijai Rayon wrote the Attorney General of the LSSR a petition, as follows:

"On March 20, 1983, while returning to his parish from a retreat, Father Juozas Zdebskis of Šlavantai was detained by the militia.

"When he did not show up for Mass, a group of the faithful went looking for the priest. Noticing his automobile in front of the Lazdijai branch of the Ministry of the Interior, the faithful charged into the militia station and demanded the release of the priest, who was being crudely blackmailed, detained and persecuted, unfortunately not for the first time.

"However, the militia and KGB ordered everyone to disperse quickly and a few people were arrested for allegedly disturbing the peace, among them Antanas Grigas, a teacher at the Liepalingis Middle School.

Byelorussian SSR

Pelesa (Varanovo Rayon, District of Gardinas).

In 1962, the Soviet government demolished the steeple of the church in Pelesa, and converted the church itself into a grain elevator. For this viable Lithuanian parish, it was an unspeakable pain and a festering wound, because the residents of Pelesa had erected this noble church with their bare hands and their own funds. Disbelieving that the government would restore the church to the faithful, the people of Pelesa nevertheless tried to get the ear of the highest government agencies. This is an example of special deafness on the part of the government:

Since 1976, the people of Pelesa have sent thirty-three petitions to Moscow and Minsk. The first time, twenty of the faithful signed a petition to the Deputy for Religious Affairs in Minsk; and the second time, to Moscow, six hundred of the faithful. The response was, "We do not forbid you to pray in neighboring churches: in Polish, in Rodūnė (the furthermost villages being 25 km away), and in Lithuanian in Dubičiai (30 or more km away)." To other petitions they would not reply, or they would repeat the same answer.

In 1983, the church as a warehouse was empty. In the center of Pelesa, and Bolcheska (the communal farm center), are great warehouses with capacities of up to one million tons of grain, and these warehouses have not been completely full, while in the church they stored just a couple of tons of grain. Since March 1 there has been no grain in the church.