The Crime

During my twenties I worked at the most menial tasks, holding clerical and factory jobs, so I could go to church and pray without trepidation. In 1970, however, I took work in the computer center of the University of Vilnius Physics and Mathematics Department under the title of Senior Engineer, with the duties of key-punch operator, earning about 100 rubles a month. But I had to leave that position because the university rector called me in and told me that if I did not resign, it would go badly for him. I did not want him to suffer, so I drafted my resignation, and they terminated me "at my request". Here is what happened...

In 1970, when a criminal case was brought against Father Antanas Seskevicius for catechizing children, I hired an attorney for him. But to sympathize with and help those who are being persecuted by the KGB is to make oneself a target of the KGB.

Father Seskevicius' trial took place in Moletai on September 7 and 8,1970. When we entered the courtroom the first day of the trial, we saw that all the seats were already taken by KGB agents, militiamen in mufti, and several women wearing heavy makeup. Witnesses, friends and acquaintances of the priest, only a small number of whom gained access to the courtroom, had to stand throughout the trial.

The trial lasted from 9:00 AM until 6:00 PM. Among the witnesses were some elderly mothers of large families, exhausted by communal farm work, including one mother of four recuperating from abdominal surgery, and also one war veteran missing a leg. When I suggested to the young men who were seated that they should allow the tired mothers and invalids to have a seat, they angrily retorted, "If they're tired, let them get out... nobody is keeping them here... ." The poor men did not understand that all those people had been brought here and were being kept here by love and respect for the priest. Bored, they paged through newspapers and talked among themselves, paying no attention to the trial, while cynically ridiculing the faithful who were saddened and concerned about the priest's fate.

Summoned to the trial as witnesses were about seventeen children, ages seven to ten, and their parents. Even before the trial, the children were threatened by the principle of the Dubingiai Primary School and several chekists.1 Pushing and even striking the children, they pressured them to sign edited statements alleging that "in the church hall the priest taught children religion." Of the seventeen, only four signed, but even these four stated during the trial that they had signed under duress, not even knowing the contents of the statement.

All the witnesses, including the children, were isolated from one another until their appearance on the stand. The officials intimidated and threatened the children and the parents in all sorts of ways, demanding that they testify that the priest had taught the children religion. However, the parents all testified that they themselves, or close relatives, had taught the children

1Chekist—another name for a KGB agent, from Cheka, the former name of the KGB.

religion, and the priest had only tested their knowledge. Therefore, they asked that they, the parents, be sent to prison, and not the priest. However, no one paid attention to them.

Summoning the child witnesses one by one, the judge told them, "It is good that you studied religion. It is necessary to study. I studied myself. After all, the priest taught you, didn't he?" The children were very frightened, many of them wept, but all of them replied that it was not the priest who had taught them, but rather their mother, father or grandmother.

After the trial, the four children became seriously ill. Feverish, weeping and restless, they shouted that they were afraid of the militiamen.

After the first day of the trial, Father Seskevicius offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in the evening, with weeping parishioners participating. During the sermon, he asked all of the faithful to respond to hatred and injustice with love and prayer, according to the example of the crucified Jesus Christ. Kneeling at the foot of the cross, the children thanked God for helping them not to be afraid of the officials' threats and to tell the entire truth in court.

The second day of the trial even fewer people were allowed into the courtroom, and only officials were given seats. They abrogated the priest's right to present witnesses. Hardly had the court recessed when two militiamen burst in and, without explanation, escorted the only witness present out of the courtroom. Immediately afterwards, the Assistant Chief of the Moletai Militia, Tamosiunas, entered the room, chekist agents standing at the door pointed at me and said, "Grab herf

Tamosiunas seized me by the hand, which I disengaged, but two militiamen sprang forward, twisted my arms behind my back, and took me from the courtroom. They seated two of us in an automobile, and Tamosiunas drove us to a militia station. The militiamen joked that it had been planned ahead of time to escort two of us roughly from the courtroom, in order to frighten all the others.

The other woman detained was the mother of four children; she had recently undergone abdominal surgery and her third daughter, little Therese, after being frightened the day before in court, was very ill. I explained all of this to the chief of militia and asked him to release her since he knew what sort of "offenders" we were. He mocked me, but a half hour later, he put the woman on a bus to her collective farm, ordering the driver not to let her off along the way, lest she return to the trial. The woman was very pale, and weeping from fright.

After the trial was over, and the priest had been taken off to the Lukiskiai Prison in Vilnius, Tamosiunas returned to the militia headquarters and bragged to me, "We sentenced the priestr He had received one year of hard labor, and Tamosiunas explained that they had detained me because they wanted peace and quiet in the courtroom. Yet in the courtroom, no one had caused a disturbance, and the judge had not warned me once.

When Tamosiunas began to make fun of the Faith, I told him that you cannot make fun of something with which you are not familiar. Tamosiunas replied, "You are well read on the subject of religion, but Ragauskas was smarter than you. Have you read what he has written?"

"Yes, I have read his books, but before death, he regretted that he had written so and called for a priest, but two chekists guarded the entrance to his ward and would not allow any visitors in. The hospital personnel heard how he prayed out loud, reciting the Miserere and other penitential psalms."

Tamosiunas was surprised, and after a moment of thought said, "Ragauskas prayed before dying because he had become senile."

Surprised, I asked, "Just a few months before Ragauskas' death, an article was printed in the republic newspaper under his by-line. They don't print articles by senile writers, do they? Ragauskas was only sixty. He was suffering from abdominal cancer and could not have become senile in two months after writing the article."

Tamosiunas did not answer, but changed the subject. Thus, he was the first of the government atheists to bear witness publicly (in the presence of all those militiamen) that the ex-priest Jonas Ragauskas had prayed before his death. May the Lord have mercy on his soul.

After that, Tamosiunas returned my purse and internal passport, which he had taken when he was escorting me from the courtroom, first making a notation from the passport for the Vilnius KGB. I was already preparing to leave, when suddenly the door opened and the Chief of the Moletai KGB, intoxicated, stumbled into the room. Seeing me, he lurched nearer and banging his fist on the table, shouted, "Why have you come here? What do you want here? Why are you defending him? What is he to you? Do you know that he has blood on his hands?"

His anger was so great that as he shouted, his spittle flew in all directions. The militiamen who had been in the room slunk off to the side. I calmly explained to him that my late mother and Father Seskevicius had been students together at the Birzai High School, so she knew him well, and always respected him. And I also respect all priests.

He went on shouting that he knew everything about me, that he had recordings of my conversations with the priest, and so on.

"I'm not the least bit interested in what you have," I replied. After a while, when I continued answering him calmly, the KGB chief quieted down. But it was midnight before they released me from the militia station.

For the first time, I felt how unfortunate are those who do not have faith or love. I saw how the suffering of Father Seskevicius—his imprisonment—accepted with love, touched then-hearts and consciences. Would that more people could be found determined to go to Golgotha with Christ and to die with Him.

Harassment and Arrest

Very soon after the trial, I was summoned to the Vilnius KGB, where chekist Gudas and chekist Kolgov reprimanded me for daring to engage an attorney for Father Seskevicius. Gudas threatened to throw me out of work, to take away my cooperative apartment, to expel me from Vilnius, and to "take care or my brother Jonas Sadunas. When I refused to be intimidated, Gudas began shouting, "Well bring a case against you, like the one against Seskevicius, and you'll go to prison with himP

I replied that I gladly agreed to suffer for the truth. At this, Gudas could not restrain himself and slamming the door, he stamped out of the office. Convinced that I had not been intimidated by their threats, they released me, but from that time on, they followed me at every step.

I noticed this only during the summer of 1974, prior to my arrest. It seemed that two or three KGB agents were following me everywhere. Accordingly, I prepared myself for a raid by destroying or hiding everything that in the event of my arrest could cause unpleasantness for others—letters written to me, addresses, peoples' work or home telephone numbers, etc.

On August 27, 1974, after praying in the chapel of the Mother of Mercy of the Dawn Gates, I came home with number 11 of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania,2 planning to copy it. Along with it I brought home the small typewriter which the late Canon Petras Rauda had given me. As I entered my apartment at Architektu 27-2, I met my brother on his way to the Polyclinic. I did not have a chance to speak with him.

In my room about 2:00 p.m., I began copying the Chronicle. Hearing me, a neighbor woman, a teacher named Mrs. Aidi-etiene, who was an informer I did not suspect at the time, called the KGB and told them I was typing. (Chekist Vytautas Pilelis mentioned this to me during my interrogation: "You sympathize with everyone, but no one sympathizes with you. You had hardly started typing the Chronicle when the woman next door immediately informed us of the fact, by telephone." I replied, "If she did so convinced that she was doing right, I respect her. And if she did it for spite, I am sorry for her")

When the chekists came and surrounded the house, that same neighbor hurried at their orders to the Polyclinic to find out whether my brother would be returning home soon, since the chekists had decided to enter the apartment at the same time as he, and so to surprise me while I was typing. And that is exactly what they did. About 4:00 as soon as my brother returned, a whole group of chekists tumbled into our apartment. Three of them opened the door to my room, and saw me sitting at the typewriter, talking with Brone Kibickaite, my best friend, who was sitting nearby, and they began shouting, "Don't move! Hands up!"

2The Chronicle is an underground, periodical account of the Lithuanian Catholic struggle to survive under an atheistic and totalitarian regime. It is circulated through the diligent efforts of those in the resistance, who type multiple copies for private distribution. Word processors and copying machines are unknown in such circles.

Smiling, I asked them, "Why are you shouting so? Have you seen an atom bomb?" I said this so calmly that Brone thought that some acquaintances of mine had come in and tried to frighten her. She asked them, "And how did you get here?"

They did not answer her, but only stated that they had a search warrant and were going to use it. They advised me to surrender anything incriminating. I stood up and said, The thing you are most interested in is the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania. Here it is. You won't find anything else here."3

"Sit down at the typewriter!" the chekists shouted. "We want to photograph you."

"If you want a photograph, sit down yourselves," I replied, and moved away.

They told Brone and me to stand in the corner and not to move about. They started to search, and we two, in order not to waste time, began praying the rosary aloud, saying, "You go on about your work while we pray."

3According to the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania (No. 28, June 29, 1977), one of the KGB agents said to Nijole: "You are a Catholic. How can you type the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, which contains only lies and slander about the so-called persecution of believers?" She replied: "The accuracy of every atheist misdeed revealed in the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania is confirmed by the tears of the faithful."

The agents also maintained that the article on the funeral of the late Canon Petras Rauda had probably been written by Nijole. She denied this allegation, saying that if she had written it, she would have included many more details about the harassment by KGB agents during the funeral. Later, as the chekists began to ridicule the late Canon Rauda, Nijole was outraged: "All of you together are not worth a single toe of Canon Rauda!"

The poor chekists felt very uncomfortable, because instead of being afraid of them, we calmly prayed. In the middle of the search, the chekists took Brone Kibickaite, and carried out a search of her apartment (Tiesos 11, apartment 38) but they found nothing "illegal". Still later, they took my brother to the KGB office, so that they could later carry out a search of his room without him, without me and without a warrant, completely ignoring my strong protest against the terrorizing of my sick brother. Chekists can get away with anything.

During the raid, the chekists seized three different issues of the Chronicle. Later, they took anything they wanted, without showing it to me, or entering it into the search report. In this way, my notes with thoughts on religious topics, photographs and other papers disappeared. But addresses of my friends and correspondents were well hidden, and they did not find them.

Suddenly one of the chekists began rejoicing that he had found some letters I had written. "Letters.!" he shouted. I jumped up to him suddenly and grabbing the letters from his hands, I tore them into bits, while the chekist shouted, "Give them back!" I quickly ran to the hallway toilet next door and with a resounding flush, sent everything down the sewer. The chekists had not expected such sudden action on my part, and when they realized what was happening, it was too late. In this way people who had written to me were saved from interrogations and perhaps searches.

When they came to their senses, the chekists surrounded me shouting that they would take me away to the KGB headquarters and finish the search themselves. "You can take me," I said, "I am satisfied now that no one will suffer on account of me." However, they did not take me away and the search continued to the end. Into the room came chekist Kolgov, who smugly stated, "Four years ago we warned you. Since then we have been following your every step. . . . You did not mend your ways. Now you're going to get it...."

"According to the Russian proverb," I told him, "one waits three years for a promise to be fulfilled. But I wait four years for you to put me in prison. You're late!"4

4Nijole was charged with violating paragraph 68 of the Criminal Code of the Lithuanian SSR—anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.

Kolgov became confused and began denying that they had ever promised me anything, claiming that I was imagining things.

"It's good," I said, "that you have warned me in time with whom I am dealing. Now I will not speak with you at all, lest I 'dream something up again'." Thus was born my firm resolve not to speak with those slaves of falsehood, the chekists, about any aspect of the case during interrogation.

After the search, three chekists accompanied me to KGB headquarters, and the others, remaining behind in my apartment, carried out the search of my brother's room, without finding anything "illegal". Meanwhile Lieutenant Colonel Petruskevicius, who had led the raid, began interrogating me. In response to his question, "Where did you obtain the Chronicle," I replied, "I'm not going to answer any questions concerning the case because you yourselves are the criminals, crudely transgressing the most elementary rights of the faithful guaranteed by the Constitution, the Declaration of Human Rights, and by statute. So I express my protest against the case. I will not assist criminals in the commission of a crimer!"

"For that, we'll shut you up in a psychiatric hospital," threatened Petruskevicius. "There it will be a hundred times worse than prison." But I did not become frightened, and he promised to let me go if I told him from whom I obtained the Chronicle. I kept silent.

In this way chekists are always breaking the law during investigations, and all of them should be brought to criminal trial according to Par. 187 of the Criminal Code: "The use of force by a person carrying out a search or preliminary investigation to compel one to testify, or forcing one to give testimony during a trial, by using threats or other unjust actions, is punishable by deprivation of freedom for up to three years. The same holds in connection with the use of deceit and with ridiculing a person under interrogation—punishable by deprivation of freedom for three to eight years."

However, this is only on paper while in reality, during the entire occupation of Lithuania, the chekists have deliberately broken this law, and not one has ever been brought to criminal trial, since everything is based on lies and deceit.

Failing to get anything out of me during interrogation, chekist Petruskevicius ordered the soldiers to take me down to the KGB cellar—to solitary confinement. A woman came in, searched me, taking away everything, even the cross from around my neck, my rosary and a medal. Afterwards, they took me to a separate corner cell where they kept me about seventeen days.

Interrogation:

The Cellars of the KGB

In the cellars of the KGB—the interrogation solitary section—the old methods of torture used during interrogations as described in the Gulag Archipelago have been changed for a new kind. In the KGB cellars are hot cells and cold cells. They kept me, Vladas Lapienis, Father Alfonsas Svarinskas (1983) and many others in hot cells where one is constantly being stifled from lack of air and from heat, perspiring ceaselessly.

On the other hand, Genovaite Navickaite, Ona Vitkauskaite and others were kept in cold damp cells with water dripping from the walls. There it was so cold that they were frozen to the marrow, and their joints ached. Moreover, they felt so weak that they could hardly walk. They suffered from severe and unexplainable headaches and stomach cramps, and when they lay down, they lacked the strength not only to get up, but even to move a hand. Only after some time would they gradually recover.

Vladas Lapienis was kept for a long time in a cell where his whole body began aching. When he scratched himself in his sleep, festering sores would appear. He began having heavy nosebleeds, and to feel severe anxiety, fear of the door being opened, etc. When he became extremely weak and asked during interrogation whether, upon his death, his remains would be turned over to his wife for burial, the chekists took him to another cell, where all these problems vanished.

Vladas Lapienis suffered from hypertension, but after interrogations, and even now that he has returned from Siberia, his blood pressure is constantly very low. Only God knows what chekists use in their desire to break the will of those under interrogation. Moreover, they keep you all the time in a cell with a KGB informer, usually a criminal offender, who, when discovered, begins to rage and to harass you in every way.

The KGB cells are deep underground, and only the top of a small window at the ceiling reaches the ground outside—the pavement of the KGB yard. The little window is barred with double panes of filthy glass, and you can barely see a patch of sky. To reach that window, one must climb up on a small table, and this is strictly forbidden.

Those under interrogation are taken outside for a half hour of exercise daily (it is supposed to be forty-five minutes, but the soldiers cheat on the time) in the little yard, similar to a cement cave—with high cement walls and floor, and above bars with narrow apertures. The little yards are four by five paces, or a bit larger. All around are the high walls of the KGB headquarters. Throughout the interrogation period, one does not see a tree or a blade of grass.

In the corridor of the interrogation-isolation section, three military guards pace ceaselessly, and they are constantly looking into the cell through a small "eye" in the door. Among themselves they curse and swear, especially the most vile Russian profanity, cursing one's mother. When I complained to Major Pilelis about the cursing of the Communist Youth League soldiers, he told me with a smile that there was no harm; they do not know how to talk in any other way, and use profanity as a connective between words. Such is his Communist morality, to curse everything noble and sacred, and only when mingling with foreigners to don the deceiving mask of culture.

How sad that there are still people abroad who believe the lying promises, agreements and "good-will" of the Communists. The Communists promise much, in order to cause the lowering of one's guard, and later, to cause greater harm—to swallow a larger bite. All of the agreements and documents they sign are mere deception, immediately broken in the most cynical fashion. Every dialogue with Satan, or his willing slaves, is a crime. True love does not consist in helping them to do evil, or in believing in their lies, but rather, in boycotting evil. The Communists, like the serpent in the Garden of Eden, promise much, but bring death.

Even though it was very hot in the cell, and there was no ventilation, my morale remained good because they had taken me alone and I had not involved anyone else. In thanksgiving to God, I sang hymns, and the guards banged on the cell door, shouting for me to be quiet. Because I would not obey them, they wrote me up in a report to the chief of the isolation section, and personally complained, "They've brought us a long-playing record, and there's no way to stop it."

Soon after, I began losing hair dramatically, and losing weight. The KGB has ways of wearing down those under interrogation, with the idea that as one is physically weakened, the will is also weakened. But they do not know that even the weakest person, supported by Christ, is unbreakable.

Petruskevicius interrogated me for about two months, and when he could not get me to talk, he gave up on my case. He also threatened me constantly with the psychiatric hospital, and he ridiculed all believers—"You are cowards! As soon as you wind up with us, you all head like rabbits for the bushes—You keep quiet, you don't answer questions, you give no testimony. Revolutionaries used to make the courtroom their tribunal. They used to speak the truth to your face. But you are cowards. ..."

"Don't laugh at believers," I advised him. "You had better pick up the Scriptures and read the passage about David's battle with Goliath. It is most apt for the present situation. You, the KGB, are symbolically that Goliath today. Thousands of staff persons, hundreds of thousands of agents and informers—you have all the best means of detection and eavesdropping; in your control is all the power: the army, the militia, the prisons, psychiatric hospitals. As for deceiving the people, you have had special training in that and twenty years of practical experience, while we believers, weaker than little David, not only lack a slingshot and a stone, but you have even pulled the little crosses from our necks.

"Nevertheless, we, just like the little David, go up against you in the name of the Lord of Hosts, and if the good God wishes, we will have our day in court. Just wait a little...."

And the good God did bless us. Despite the secrecy of my trial (only a few chekists were present) my words during the trial very quickly became known world-wide. "If God is with us, who can be against us?" He chooses the weak things of the world to shame those who think they are something. To Him alone be glory, thanks and love for all ages!

But this was in the future. For the present, Rimkus struggled with me for about two months, and not getting anything out of me, turned me over to the Assistant Chief, Kazys, of the Interrogation Section.5 The very first day, when chekist Kazys received no answer to a question in connection with the case, he began shouting, "You schizophrenic!"

5According to the Chronicle, No. 28: "The interrogators [also] questioned many witnesses. Nijole's relatives were summoned, as were her acquaintances, but they still found no evidence against her.

At the beginning of 1975, the KGB intercepted a letter from Poland addressed to Nijole. Henrik Lacwik was not aware that she had been arrested. In his letter to Nijole, he wrote about his 1974 stay in Lithuania. In February, 1975, the KGB agent Platinskas travelled to Poland to see Lacwik. The KGB agent asked about his visit to Lithuania, and also whether Nijole had spoken about the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, persecution of the priests or believers in Lithuania, and whether she had given him any reading material. The replies were negative.

The KGB was aided by Nijole's cousin, Vladas Sadunas, and ... on March 25,1975, Regina Saduniene (wife of Vladas Sadunas) took issue No. 8 of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania to KGB headquarters, although at the trial she would testify that she had found the said issue on her husband's desk, but did not know where it came from. Nijole had not given her anything to read.

"It seems as though you are not only the interrogator, but also a psychiatric genius," I told him in surprise. "You've hardly even seen me, and you are so firm in your diagnosis...."

"Yes, I am a psychiatrist," Kazys confirmed, "and when they take someone to the crazy house, I am the first to sign."

"To my knowledge, schizophrenics are most often victims of a disease of megalomania. Since you consider yourself to be a genius, it would be best for you to take care of your health," I advised him. Kazys blanched from anger and began pacing about the office. After that he began to threaten and intimidate, and even to show me pictures of Lithuanian partisans which had absolutely nothing to do with my case.

They questioned me the entire day, and when a soldier escorted me in the evening to the KGB cellar—my prison—I requested paper and wrote a protest to the prosecutor, with copies to the chief of the KGB and to the chief of the interrogation section.

In my statement, I protested against the hooliganism which the chekists Lieutenant Colonel Petruskevicius, Major Rimkus and Kazys engage in during interrogations. They force people to make statements by threatening confinement in the psychiatric hospital. In my petition, I emphasized that I was not opposed to psychiatric expertise, but only against the chekists' constant ridiculing of human dignity. I said that it would be better for them to beat me, because physical wounds heal more quickly than moral traumata. I refused to go for interrogation unless the investigators put a stop to this hooliganism.

For about two weeks, they did not take me for interrogation, and after that I received from the KGB Prosecutor, Bakucionis, the following reply: "Investigators have the right to make psychological tests, but in this case they see no need."

Kazys interrogated me just one day. After Bakucionis' reply to my protest, the much-touted chekist, Vytautas Pilelis, began interrogating me. When the soldier took me to the interrogation, Pilelis asked, "So you're complaining, are you?"

"I am not complaining, but protesting," I answered.

"You see," said the chekist, "I have been working here for over twenty years. Fve seen all sorts of iron men during that time ... for a week or two, they would maintain some spirit, but after that all their chins were dragging on the ground. But it's already the fifth month that you, under these conditions, have been walking around from morning till evening, smiling. We've never seen anybody like you."

"It was not on account of my good spirits that your chekist colleagues have threatened me with confinement in the psychiatric hospital, but because I won't make statements for them," I interrupted Pilelis.

"So, if you would give us just one statement, we would let you go home," Pilelis deceitfully promised.

"If you gave me eternal youth and and all the beautiful things in the world for one statement which would cause some trouble, then those years would turn into hell for me. Even if you kept me in the psychiatric hospital all my life, as long as I knew that no one had suffered on my account, I would go around smiling. A clear conscience is more precious than liberty or life. I do not understand how you, whose conscience is burdened by the spilled blood and tears of so many innocent people, can sleep at night. I would agree to die a thousand times rather than be free for one second with your conscience?

Major Pilelis blanched, and hung his head. Momentarily, he seemed petrified. I understood that he recognized the depths of his depravity, but lacked the strength, or perhaps, the will, to rise from that quagmire. (On my return from Siberia, I found out that Pilelis' past is truly terrible.)

After some time, the poor chekist picked up his head and angrily threatened, "If that's how it is, then well kick you out of here right now, and using your name well carry out raids and arrests as though you did betray people. (Here, he named a whole list of the best people.) It would be nothing for us to forge your signature under the records. So you see, your friends will turn their backs on you as a traitor, and we won't give you the time of day."

"You frighten me," I smiled. "Let everyone turn away from me. I don't need people's approval. The only thing I need is a clear conscience. As for your time of day, keep it?

"We know everything now, anyhow," Pilelis persisted.

"If you know everything, then why are you questioning me?" I asked him.

"Not everything," he hedged, "but a lot."

To intimidate me, he began to tell me, "On such and such a day, at such and such a time, so and so (all accurate) came to see you, and you served them a prune compote." I felt uneasy, not wishing to implicate innocent people. Mentally, I prayed to God to help me, when I suddenly remembered a very humorous incident which had just happened in the cell, and burst out in the most spontaneous laughter.

Pilelis had expected anything but this laugh of mine. He was so distracted and confused that he fell silent, gaping, and looked at me very surprised for a few minutes. He knew that what he had been telling me caused me no laughter. He must have thought that I was acquainted with the legal nicety that whatever the chekists discover in snooping around has no legal value until people themselves, frightened by the chekists' knowledge, admit it. But in reality, I did not know that. From that time on, for the next six months of interrogation, Pilelis did not once mention what they had discovered in spying on me.

One day, he began to praise me profusely, "Throughout my career, I have never met anyone like you, who has done so much good for people."

I asked why he was praising me so highly.

"It's not flattery, but the truth," said the chekist.

"And in spite of the fact that I have really tried to do only good for everyone," I said to him, "at my trial, you are going to give me a greater sentence than you do murderers."

"Yes, you are going to get more than murderers, because you know too much," affirmed Pilelis.

The next day, he called me and other believers who had been arrested—the late Father Virgilijus Jaugelis and Petras Plumpa—fanatics. "That appellation fits you, yourselves, best," I told him, "because you try with all your might to make us atheists, but believers love all people because Jesus Christ said, 'What you do for anyone, you do for me.' We fight only against evil. For you we feel sorry, and if necessary, we would give our lives for you. You know that?

Yes, Pilelis knew it, but in spite of that, he wrote in the space specially left in the witnesses' depositions, after they had signed them and departed, that they had testified that I was a fanatic. I saw that falsification when I looked over the case against me before the trial. On my return from Siberia, I asked those witnesses whether they had said I was a fanatic. Not one of them had said so, and some of them did not even know the meaning of the word. The chekists charge everyone who is on trial for religion with religious fanaticism. From this it is clear that there are secret instructions from Moscow to this effect.

One time, when a soldier brought me for interrogation, there were two other chekists in the office with Pilelis. This used to happen often, because Pilelis mentioned that he is afraid of me, since during the raid I had been able to destroy letters in front of a dozen chekists. "I don't know what she might do," he has said. So we were rarely alone in the office.

In the presence of the two chekists, Pilelis stated, "You believers are never satisfied: If it's not one thing, its another. Do you think you would have fared better under the fascists?"

"I don't know what would have happened to us under the fascists," I replied, "But I do know that you are worse than the fascists."

Pilelis jumped up and shouted, "What, we are worse than the fascists?"

"Yes," I replied. "The fascists committed a great crime, but they did not hide it. They stated openly whom they destroyed, whom they intended to enslave, and everyone knew about it. You commit the same crime, but disguised as 'liberators' and 'brothers', while behind your backs you hold that same bloody knife. What could be worse in a human being than hypocrisy! Since you are hypocrites, you are worse than fascists!"

"I'm going to put that in the record!" shouted Pilelis, snatching the piece of paper from the table.

"Write it down," I calmly told him, "I will repeat everything for you, word for word, and sign the deposition."

Pilelis, however, did not have enough nerve to enter my statement in the record, and he did not write a word of it.

During the tenth month of my interrogation, Pilelis showed me a picture of myself and asked what I could say about it. I was seeing the postcard-size picture of myself for the first time, and I understood that they had enlarged it from a small passport photograph which they had found during the raid.

In order not to implicate new individuals, I said, "If this has nothing to do with my case, and you do not take down my statements, I will tell you what I know about this photograph."

Pilelis assured me, T give you the word of an investigator that this has nothing to do with your case, and I will not enter it into the record."

I told him that I was seeing my picture in this size for the first time, that someone had enlarged it from a passport photograph, reproduced it, and distributed it, so that people who did not know me could have that picture. But when I finished speaking, the chekist began entering everything in the record. "What happened to your word?" I asked him. Pilelis, smiling sardonically, said, That's called legal astuteness!"

"If you consider lying legal astuteness, then as a sign of protest, I am not going to speak to you at all, from this moment on." I remained silent two weeks.

Two or three chekists and Prosecutor Bakucionis would come to the interrogation sessions and try to get me to talk, but since I remained absolutely silent, after two weeks they closed the case. Pilelis had ridiculed me the whole time, for not knowing anything, and for not being acquainted with the legal niceties, and when he finished interrogating me, he hissed through his teeth, "Well, aren't you tough!" When they closed the case, I breathed easier. "Thank God, the terrorizing of witnesses has ended? Chekists Gudas and Vincas Platinskas contributed, but Pilelis especially. Vincas Platinskas terrorized Brone Kibickaite, even when he met her on the street: "Your place is with Nijole, in prison?

Friends and relatives left in freedom always suffer more pain and worry than the prisoner. Since I had refused an attorney, I acquainted myself with the brief against me. Of the many witnesses questioned (on the matters reported in the three issues of the Chronicle), in spite of the chekist threats, everyone testified that the reports were true, but on June 16-17, they tried me for "libel", without having a single witness.

The Trial and the Defense

I was escorted to the trial by six soldiers, while even murderers are guarded by only one or two soldiers. They were desperately afraid lest my defense speech and my final statement get out to the public.

At the beginning of the trial, Prosecutor Bakucionis, holding in his hand an envelope containing my defense speech and my final statement (which I had not been able to smuggle out of the KGB cellar) triumphantly exclaimed, "Don't say what you are prepared to say today, and you'll go home from the trial free!"

The Prosecutor in the Supreme Court offered me freedom in exchange for my silence. How much they feared the truth! I replied, "I am not a speculator, and I refuse to speculate with my convictions. I will speak today!"

The Prosecutor blanched, and hanging his head, sat down.

Sitting in the courtroom were only six chekists; I was guarded by young Russian soldiers who did not understand a word of Lithuanian, hand-picked so that they would not understand what I had said in court.

I asked the judge why the courtroom was empty. He deceitfully affirmed that the trial was secret.6

"And why do you chase witnesses out immediately after their testimony? After all, even in a secret trial, they are supposed to remain until the end. I demand that they remain in the courtroom, because I need them."

The judge angrily shouted that neither he nor I were in charge, and that we all had to obey the law.

Then the judge threatened, "One more word, and well take you away! Well sentence you in absentia?

"You can take me away," I assented. "Then your trial will be triply unjust: without spectators, without witnesses, and without me, what kind of trial will that be?"

6An excerpt from the Chronicle, July 4,1975, No. 17: "The Supreme Court of the Lithuanian SSR began considering the case of Nijole Sadunaite on July 16, 1975. The session began at 10:00 AM. It was chaired by Kudiriashov; the state Prosecutor was Bakucionis.

"The following witnesses were summoned to appear: Jonas Sadunas (Nijole's brother), Vladas Sadunas (her cousin), Regina Saduniene (Vladas' wife), Povilaitis (the principle of the middle school), Kusleika and Brone Kibickaite.

"At the start of the session the witnesses were isolated and were ordered out of the courtroom after giving their testimony, so they could not follow the court proceedings.

"Only six soldiers and five KGB agents were in the courtroom. The chief judge allowed only Jonas Sadunas, Nijole's brother, to remain; outsiders were not permitted to enter. KGB guards informed them that the court proceedings were closed."

Nijole refused to accept the services of an attorney, lest anyone get in trouble as she had for assisting Fr. Seskevicius at his trial; she also refused to answer the questions of the court. Of all the witnesses, only one testified that Nijole had given him copies of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, and even he admitted later (while intoxicated) that he did so in fear of the KGB. Nijole protested several times against the judge's abuse of the law, whereupon the prosecutor recommended a sentence of four years at hard labor followed by five years in exile.

They allowed me to remain in the courtroom, to their extreme regret. When I began my defense speech, the prosecutor, the judge and associate judges hung their heads and lowered their eyes:7

I would like to tell you that I love all of you as my brothers and sisters and, if need be, without hesitation, would give my life for each of you. Today, that is not necessary. But I must tell you the sad truth to your face. It is said that only he who loves has the right to criticize and scold. In addressing you, I make use of the right. Each time people are tried in connection with the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, the following words of Putinas8 seem most appropriate:

"In arrogant tribunals

Murderers condemn the just.

You trample altars,

Both sin and righteousness

Collapse under the weight

of your statutes."

7Judge Kudiriashov and Prosecutor Bakucionis were aware of the content of Nijole's defense speech and, fearing lest Nijole's speech be heard by witnesses, cleared the courtroom and only allowed her brother to remain. (Chronicle, No. 28, June 29,1977)

8Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas, Lithuanian poet (1893-1967).

You well know that the supporters of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania love their fellow man and are struggling only for their freedom and honor, as well as the right to enjoy freedom of conscience, which is guaranteed to all citizens without regard to their beliefs by the Constitution, the law and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They are seeking to ensure that these will not remain just beautiful words on paper nor lying propaganda, as at the present, but will really be put into practice. The words of the Constitution and the law are important even if they are not applied in real life and the all-pervasive discrimination against believers is sanctioned. The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, like a mirror, reflects the crimes atheists perpetrate against believers. Immortality is not captivated by its own loathsomeness; it is horrified by its own reflection in the mirror.

The mirror, however, does not lose its value. A thief steals money; you rob people by taking from them that which is of greatest value—loyalty to their own beliefs and the opportunity to pass that on to their children—the younger generation.

The fifth article of the Convention in the Area of Education9 guarantees the right of parents to determine their children's morals and religious education according to their own beliefs. Nevertheless, Mrs. Rinkauskiene, a teacher interrogated in my case, states in the record that "Since there is a single Soviet school system, there is no need to confuse the children and teach them hypocrisy."

Who teaches children hypocrisy? Is it parents, who are guaranteed the right to raise their children according to their own beliefs or teachers like these? Parents and not teachers are for some reason blamed when children, whose parents have lost their authority through the influence of the school, go to the dogs.

In the record of her interrogation, Miss Keturakaite, a teacher at Klaipeda Middle school No. 10 states: "Since I am a history teacher, I have occasion to explain questions of religion to my students. In explaining the origins of Christianity and at the same time the myth of the origins of Christ...."

How can Miss Keturakaite explain questions of religion which are outside her area of competence, when she is illiterate even in the area of history, since she still maintains the obsolete atheist lie that Christ is but a legend. Such illiterates educate the younger generation and use their authority as teachers to instill lies in the consciousness of their students.

9 An intentional convention signed by the USSR.

The interrogators, Lieutenant Colonel Petruskevicius, Chief of the Interrogation Subsection Rimkus and Deputy Chief of the Interrogation Section Kazys, threatened many times to put me in a psychiatric hospital because I did not answer their questions, in spite of my explanation that my silence was a protest against this trial. Having tired of these threats, I wrote letters of complaint to the state prosecutor of the republic, to the chairman of the KGB and to the chief of the interrogation section, requesting that the latter place the letter in the record of my case. The letter was not placed in the record. But Deputy State Prosecutor of the Republic Bakucionis, who is seated right here, replied in writing that they have that right to carry out a psychiatric examination, though in the opinion of the interrogators, there is no basis for one.

But you see, that was not the subject of the letter, which was a protest against the abuses of the interrogators who seek to intimidate the person being interrogated and to force him to violate his conscience. In my letter I wrote, and I quote: "Does an interrogator have the right to threaten the person being interrogated with confinement in a psychiatric institution or with psychiatric testing, when the person being interrogated refuses to violate his conscience and his beliefs?"

During my interrogation, Lieutenant Colonel Petruskevicius repeatedly threatened me with confinement in a psychiatric hospital, which would be much worse than a prison, simply because I didn't answer his questions. The first time he saw me, Deputy Chief of the Interrogation Section Kazys officiously diagnosed me as schizophrenic, as having schizophrenic ideas, and threatened to have me examined by the Psychiatric Commission of which he is a member. Major Rimkus, the chief of the Interrogation Subsection, repeatedly threatened me with a psychiatric examination when I did not answer his questions.

Is Soviet justice based solely on fear? If I am mentally ill, I should be treated, not threatened with illness. Is one at fault if one is ill? But even the interrogators are not convinced of that, since for the fifth month in a row, they are threatening me with commitment to a psychiatric institution in an effort to break my will. By such conduct the interrogators violate human dignity and I protest such actions toward me. By the use of force to elicit testimony, the interrogators violate Article 157 of the Criminal Code of the Lithuanian SSR.10

10"A person conducting an investigation or a preliminary interrogation, who during the course of the interrogation uses force, threats or other illegal means to obtain testimony is liable to three years in prison. Similar actions which include the use of force or the mockery of the person being interrogated, are punishable by from three to five years in prison."

After I sent my protest, Rimkus, the Chief of the Interrogation Subsection, reproached me for complaining and mocked me, saying: "If you react that way you are abnormal. You don't know all of the legal technicalities."

Yes, I am unfamiliar not only with the technicalities, but also with the essence of the law, since I didn't study it. However, I know now that it is normal for Soviet prosecutors to he and slander others, not only to the accused but to complete strangers. Such actions constitute spiritual hooliganism, which should be punished, since it takes longer for a spiritual trauma to heal than a physical one.

You are not concerned at all with correcting injustice. On the contrary, you tolerate and encourage it. As proof, we can note that witnesses questioned in my case, who were able to verify the facts published in the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, were first asked how the facts could have reached the editors of the Chronicle, to whom they had told the facts, who had heard them and the like.

What you fear is the truth. The interrogators didn't question or summon those who are filled with hatred for those who are of differing opinions, those who discharged Stase Jasiunaite, a teacher at the Kulautuva Middle School, for wearing a crucifix, and who mocked her in various ways and would not even hire her as the lowliest kitchen help.

The investigators did not summon Markevicius, the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Council of Workers' Deputies of Panevezys, or Indriunas, the Chief of the Finance Department, who discharged Maryte Medis-auskaite, secretary-typist with nine years experience, because she attended church.

Yet you always claim that religion is a citizen's private affair, and that all people have equal rights without regard to their beliefs. Your propaganda is beautiful, but the actual facts are ugly! The interrogators paid no attention to the crime committed by Kuprys, the principle of the grammar school at Naujoji Akmene, and the other members of the Education Department, in discharging a teacher who, while on a field trip to Kaunas with her students, permitted them to make use of a toilet in the Kaunas park where Romas Kalanta immolated himself. What a crime! It is strange that you are still frightened of the ghost of Romas Kalanta, but how is the teacher to blame?

The interrogators did not warn any of the senior physicians, who abuse their positions by not permitting the dying to avail themselves of the services of a priest, even when such services are requested by the parents themselves, or their relatives. Even a criminal's last wish is heard. But you have the nerve to mock a person's most sacred beliefs, at one of his most trying moments—the hour of his death—and like thieves you brutally rob thousands of believers of their moral rights. That is your Communist morality and ethics!

Angus, an instructor at the University of Vilnius, coarsely slandered Pope Paul VI, the late Bishop Pran-ciskus Bucys, Father George Laberge and Father Pranas Raciunas. When will that loathsome slander be retracted? It was not withdrawn because lies and slander are your daily bread.

Frightened by the ideas of Mindaugas Tamonis, an engineer working in the area of the restoration of monuments and a recipient of a candidate's degree in the technical sciences, you confined him to the psychiatric hospital on Vasaros Gatve, hoping to "cure" him of his beliefs.

Who gave you the right to tell the pastors which priests they may or may not invite to retreats or devotions? After all, the historic decree, On the Separation of Church and State, and Church and School, affirms that the state does not interfere in the internal affairs of religious groups. In Lithuania, the Church is not separated from the state, but is oppressed by it. Government organs interfere in the internal affairs of the Church and its canons in the coarsest and most unacceptable manner. They order priests around arbitrarily, and punish them with no regard for the law.

These and hundreds of other facts witness that the atheist purpose—to make everyone their spiritual slave— justifies any means: lies, slander and terror.

And you rejoice in your triumph? What remains after your triumphant victory? Moral ruin, millions of unborn fetuses, defiled moral values, weak debased people overcome by fear and with no passion for life? All of that is the fruit of your labors. Jesus Christ was correct when he said, "You shall know them by the fruits." Your crimes are propelling you to the garbage heap of history at an ever increasing speed.

Thank God not all people have been broken. Our strength in society is not in quantity but in quality. Fearing neither prison nor labor camp, we must condemn all actions which bring injustice and degradation, or which result in inequality or oppression. Every person has the sacred duty to struggle for human rights.

I am happy that I have had the honor to suffer for the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, which I am convinced is fair and necessary, and to which I will remain faithful until Ibreathe my last. Thus, pass what laws you like, but keep them yourselves. What is written by man must be distinguished from that which is ordained by God. What is due to Caesar is but the remains of that due to God. The most important thing in life is to free one's heart and mind from fear, since concessions to evil are a great crime.

They sat there, pale, not once raising their eyes, like criminals condemned to death. I wished that I could have photographed those faces. Poor men, they realized they were committing a crime! This was noticed even by the Russian soldiers, who asked me after the trial, "What kind of trial was this? For two years, we have been escorting those on trial, and we have never seen anything like it. You were the prosecutor, and all of them were like criminals condemned to death! What did you speak about during the trial to frighten them like that?"

The second day of the trial, during my final statement, those trying me also sat there pale, with their heads drooping. Here is what I said:

This is the happiest day of my life. I am being tried on account of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, which is struggling against physical and spiritual human tyranny. That means I am being tried for the truth and the love of my fellow man. What can be more important in life than to love one's fellow man, his freedom and honor?

Love of one's fellow man is the greatest form of love, while the struggle for human rights is the most beautiful hymn of love. May this hymn forever resound in our hearts and never fall silent. I have been accorded the inevitable task, the honorable fate, not only to struggle for human rights, but also to be sentenced for them. My sentence will become my triumph! My only regret is that I have been given so little opportunity to work on behalf of my fellow man.

I will joyfully go into slavery for others and I agree to die so that others may live. Today, as I approach the Eternal Truth, Jesus Christ, I remember His fourth beatitude: "Blessed are they who thirst for justice, for they shall be satisfied."

How can one not rejoice when Almighty God has guaranteed that the light will conquer darkness and the truth will overcome error and falsehood! I agree not only to go to prison but to die, in order to hasten that end. I want to remind you of the words of the poet Lermontov11: "The justice of the Lord, however, is just." The Lord willing, God's justice will be favorable to us all. Throughout my life I will pray to the Lord for you, I wish to conclude by reading the following verses which came to me in prison:

The harder the way I must traverse,

The more I understand life.

We are all obliged to strive for truth,

Conquering evil, without regard to the

difficulty of the task.

Our brief days on earth are not meant for rest,

But to participate in the struggle for

the happiness of numerous hearts.

Only he who fully participates in that struggle

Will feel he is on the right road.

One can experience no greater happiness

Than the determination to die for others.

On such occasions one's heart is filled with joy

Which cannot be ended by prisons,

or cold labor camps.

11Lermontov, Mikhail Yurevich—Russian Poet (1814-1841).

Thus let us love one another and we shall be happy. He alone is unhappy who does not love. Yesterday, you were surprised by my happy disposition at a hard moment in my life. That proves the fact that my heart is filled with love for my fellow man, since loving others makes everything else easy!

We must sternly condemn evil, but we must also love our fellow man, even though he has erred. That can be learned only in the school of Jesus Christ, who is the only truth, way and life for all. Dear Jesus, Thy kingdom come in our hearts!

I would like to request the court to free from prison, labor camps and psychiatric hospitals all of those who fought for human rights and justice. That would be a significant contribution in the effort to spread harmony and goodness in life, and would mean that the beautiful slogan. "Man is brother to man," would become a reality.

On June 17, 1975, Judge Kudiriashov handed down the court's decision: Tor duplicating and disseminating the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, she is sentenced to three years loss of freedom, to be served in strict regime labor camps, and to three years of exile."12

12After the trial, Interrogator Pilelis confided to Nijole, "Based on the offense committed your sentence is too severe."

One patient wrote Nijole at the labor camp: "In our Soviet reality, we are accustomed to give everything different names: Truth is lying; good is evil; facts are slander. National heroes are wrongdoers or criminals."

The accuracy of these words is confirmed by the court's dealing with Nijole Sadunaite. The case was grossly fabricated, even the witnesses (Povilaitis and Vladas Sadunas) were specially bribed and coached by the KGB. For example, when drunk, Vladas Sadunas admitted to relatives that the KGB had forced him to testify that Nijole had given him several issues of the Chronicle and the book Simas to read. The relatives asked why he had not explained this at the trial. He apparently replied that the KGB would then have had his head. (From the Chronicle, No. 28)

To the Labor Camp

After the court's decision, the prison's "black raven" (the prison vehicle sheeted in black iron) returned me to the KGB cellars, but this time, very briefly—for just a couple days. The day after the trial, they granted me a brief visit with my brother, Jonas Sadunas. Before the visit, a soldier herded me to a cell in solitary, where a female KGB medical aide stripped me and searched everything in detail. I was subjected to the same "medical procedure" after the visits, also.

My brother had brought me a dark red rose, which my KGB guards examined for a long time, looking over each leaf to see whether anything was hidden there. During the visit, they seated me and my brother carefully. We were separated by a glass partition and wide table, and the prison guard did not take his eyes off us the whole time, constantly interrupting our conversation, demanding that we speak only of meaningless, everyday topics. Otherwise, he threatened to cut the visit short.

After our visit, my brother wished to give me food and clothing for the journey to the Mordovia Concentration Camp, but they would not take anything from him. The chekists told him to bring them back the next day, and then they told him that I had already been taken away, even though this was a deliberate he, for they took me away a day later. This is a standard torture—let them be hungry on the way!

Before taking me off to the concentration camp, on June 20,1975, the same KGB female paramedic searched me in solitary confinement, while the soldiers searched my meager food and clothing reserves. They even tore the wrappers from candy, and seized all of my notes. Afterwards, having warned me, "say goodbye to Lithuania, you'll never see it again! You are in our hands, we'll do what we want with your!"- they took me in a "raven" to the Lukiskiai Prison in Vilnius.

There they shut me up in a concrete cubicle—a solitary confinement cell—where one can only sit surrounded by walls and facing the door. After sitting for a while, you begin to suffocate for lack of air, but this does not bother anyone. "You didn't come to a resort!" the guards taunt you.

After keeping me in that cubicle for several hours, the soldiers herded me into a "raven", already packed with criminal offenders. To isolate me from them, they pushed me into the raven's iron cubicle, a solitary confinement compartment like a steel coffin and drove us all to the Vilnius Railroad Station.

The "raven" is windowless; you see nothing, as if you were buried alive. In the Soviet Empire, a prisoner is not a person; he is treated somewhat worse than a beast. He is a slave without rights, despised and morally and physically abused non-stop by soldiers and guards.

After bringing us to the Vilnius Railroad Station, soldiers with dogs ordered us all from the "raven". Off on a siding, out of public view, the prisoner's railroad car awaited us. Lining us up, they positioned me first, as "an especially dangerous state criminal" (the Soviet term for prisoners of conscience), with four soldiers and two guards watching me. All the others—several score of male criminals—they lined up behind me, and guarded them with just a few soldiers and a couple of dogs. The prisoners were surprised, and asked where they had been keeping me, since I was so pale and exhausted, although they themselves did not look any better.

After ten months of living in the KGB underground prison, I saw again that the trees and grass were still green, that there was so much space about and the sky was so big, not at all like what is seen through a barred little window. What a joy to see all that! Thanks to the Creator for such beauty! Only there was no time for us to enjoy it all, because they quickly herded us into a railroad car.

In the prisoner's car, behind thick steel bars, are separate cubicles with steel-barred doors, fastened with a large lock. They locked me up alone in a cubicle made to accommodate two, while the male criminals were stuffed eight, or even twelve, to a four-place cubicle. At night, a wooden bench took the place of a bed. I was able to lie down on the bench, but the male prisoners, packed like herring in a barrel, had no room to lie down or to sit.

In the corridor, in front of our pens, paced three military guards. Before my pen, a soldier stood constantly with a rifle, never taking his eyes off me, lest I "evaporate". The guard was changed every three hours. The prisoners asked them what I had done, to be guarded so. They, most of whom were four-to six-time repeaters, had never seen anyone guarded so closely. They were surprised to learn that in the Soviet Empire there still are prisoners of conscience, and all of them cursed the Soviet government which, according to them, was alone responsible for their being dehumanized.

The soldiers shouted at us not to talk, that it was not allowed, but later even they got interested in the conversation. In the hearts of most of them there still flickered a spark of humanity, but it was covered over with hatred and the ashes of various kinds of evil—the result of atheistic upbringing.

On the trip, the prisoner is given one small loaf of black bread a day, very sour and under baked (they used to give us such bread in the KGB cellars and in the concentration camp, also—this bread is specially baked for prisoners), after eating which the stomach begins to ache as though a fire were burning, and a few small soggy and very salty little fish—herring—the size of a finger.

I used to refuse this ration, and would not eat it in order to avoid agony later, although when I was free, I had been able to eat everything and never experienced stomach trouble; I had been quite healthy.

Prisoners who ate the little herring would ask for water to quench their thirst, but the soldiers would make fun of them and purposely not give them anything to drink for hours on end, saying, "Let them suffer!" In the car, such an uproar and such cursing would begin, that it was sheer hell. When they had finally had their fun, the soldiers would bring a kettle of water. After drinking it, the prisoners would soon begin to ask to be allowed to go to the toilet. Once more the soldiers would torment the prisoners, purposely not taking them for several hours.

How much cruelty there is in the hearts of young soldiers eighteen to twenty years old! Almost all of them wore Communist Youth badges—"Lenin's grandchildren". They curse and swear as much as the worst criminals. So much for Communist morality!

Sometime after we had left Vilnius, we stopped, and our car remained at the siding for a whole day. No one gave us any food rations for the following day because it had not been foreseen that the journey to the prison at Pskov would take two days. The prisoners, weakened as they were, had to fast. After I pleaded with them for a long while, the soldiers agreed to distribute to the prisoners what I still had in the way of food, but it was nearly a drop in the ocean.

The transport is a special way of tormenting prisoners. The journey is specially drawn out to a month, or even two, when normally two or three days would be enough. The prisoner's cars are overcrowded. All of the prisoners almost ceaselessly smoke the worst grade of tobacco—makhorka—and the windows in the corridor of the car are not open during the day. The glass is opaque, so that people cannot see the pale prisoners

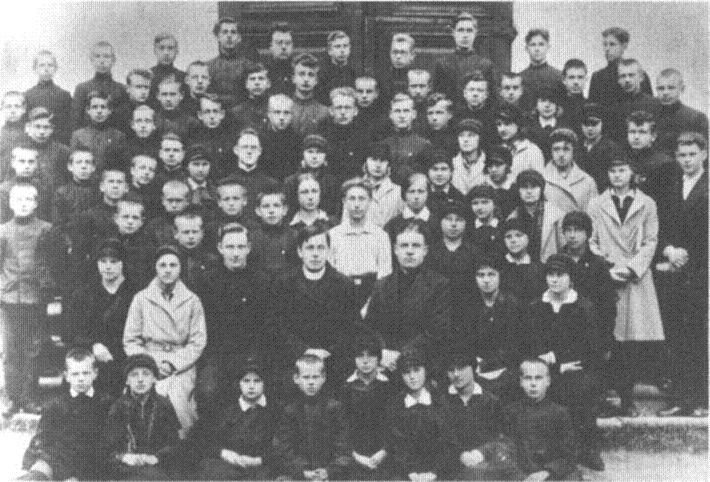

In this 1931 high school photo from a private collection are pictured Canon Petras Rauda (second row, fourth from the left), Nijole's mother, Veronika Rimkute (fifth row, second from the right), and her uncle, Kazys Rimkus (fourth row, first on the right), presently a physician in Chicago. Interestingly, Fr. An-tanas Seskevicius is also in this class (second row from the top, third from the left). It was Nijole's defense of Fr. Seskevicius which led to her being placed under surveillance by the KGB.

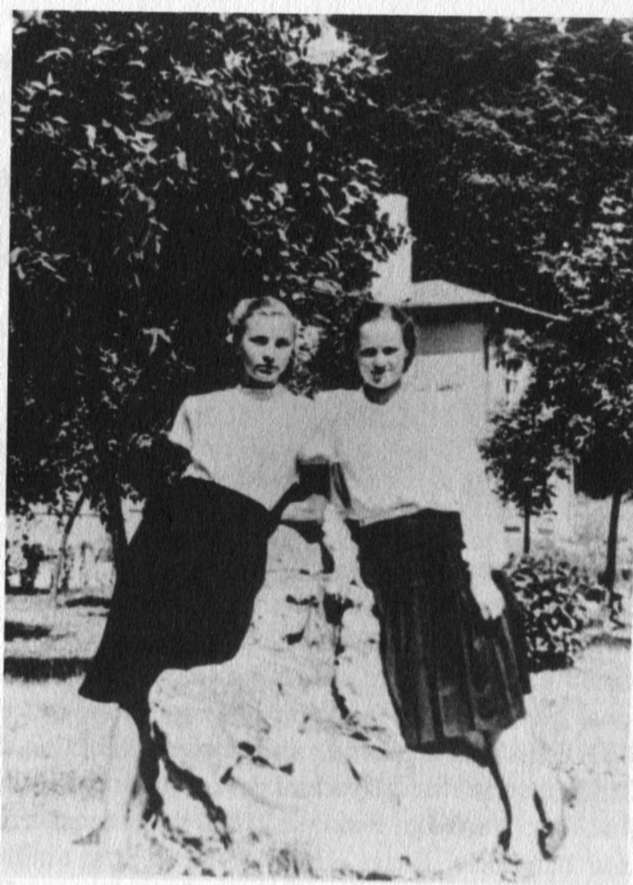

Nijole Sadunaite at age 17 (left) with a friend in the capital city of Vilnius, Lithuania, taken in May 1955. She graduated from high school the following year.

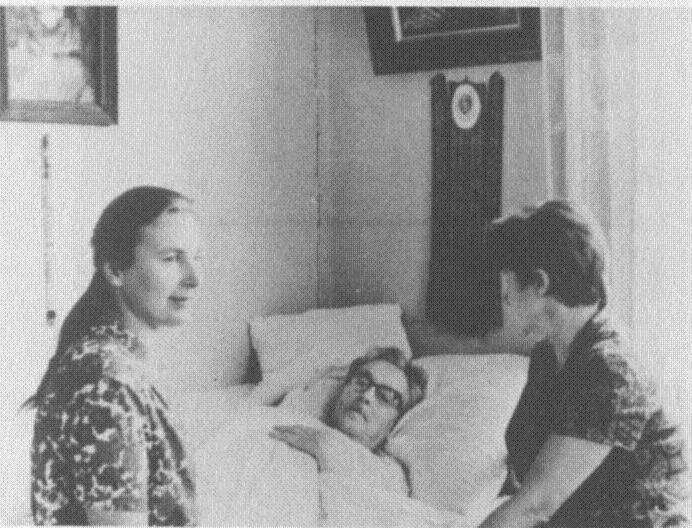

At the wake of Jonas Sadunas (top), Nijole Sadunaite's father, who died on April 29, 1963, are (from right to left) Nijole, her mother Veronika, and her brother Jonas. All three are also present at his gravesite during his funeral on May 1,1963.

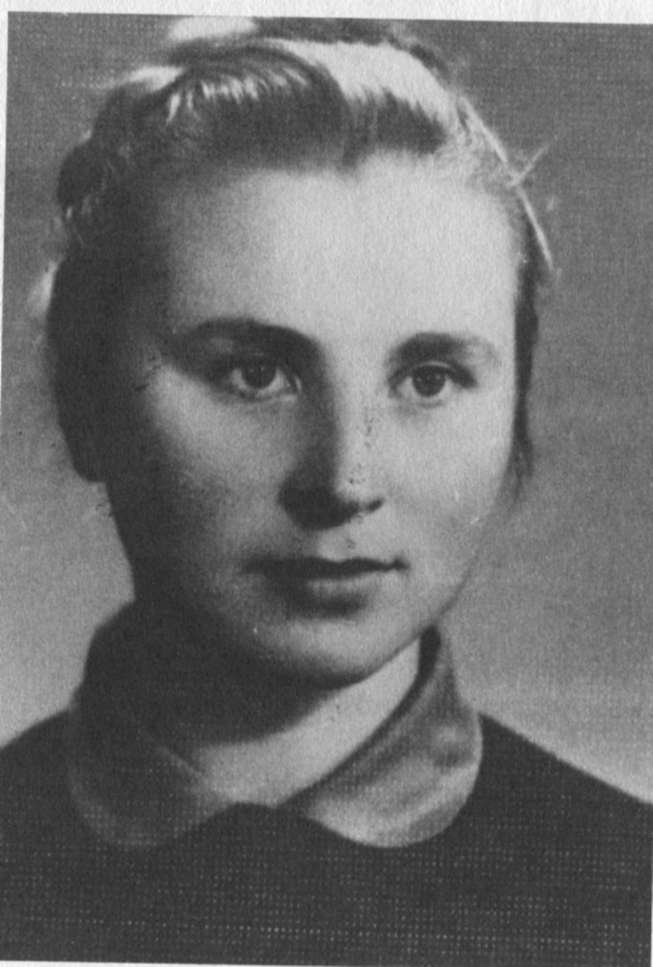

Nijole Sadunaite at age 26 in 1964.

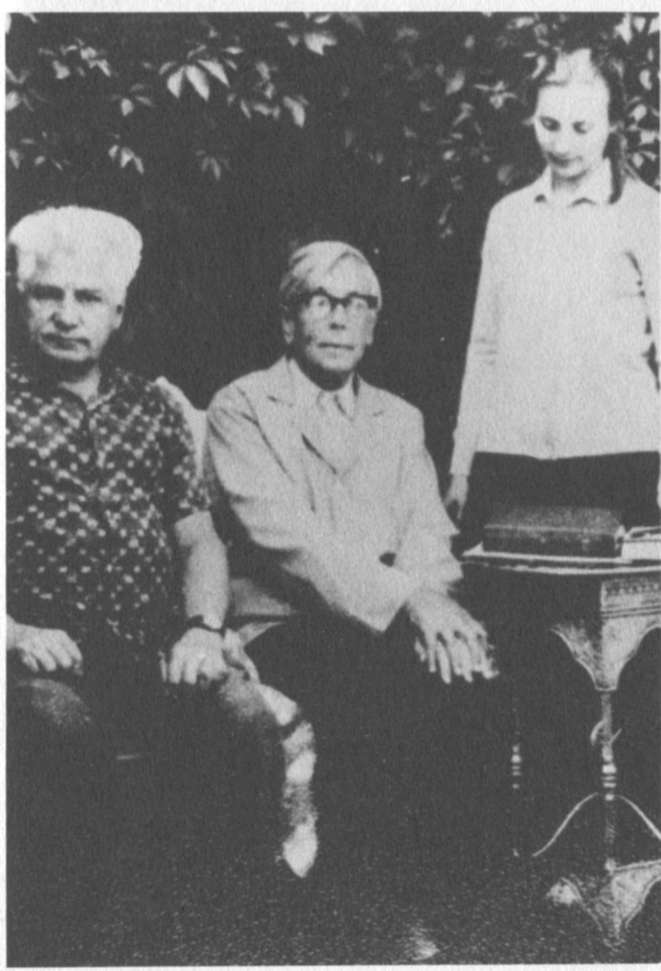

Nijole Sadunaite with Father Petras Rauda (middle), a Lithuanian high school chaplain who was a close friend of the Sadunaite family. The man to the left is unidentified.

In this photo taken in 1973, Nijole Sadunaite is nursing Father Petras Rauda during his long illness. She took care of him until his death in 1974.

This is an excerpt from Nijole's manuscript, written in her own handwriting.

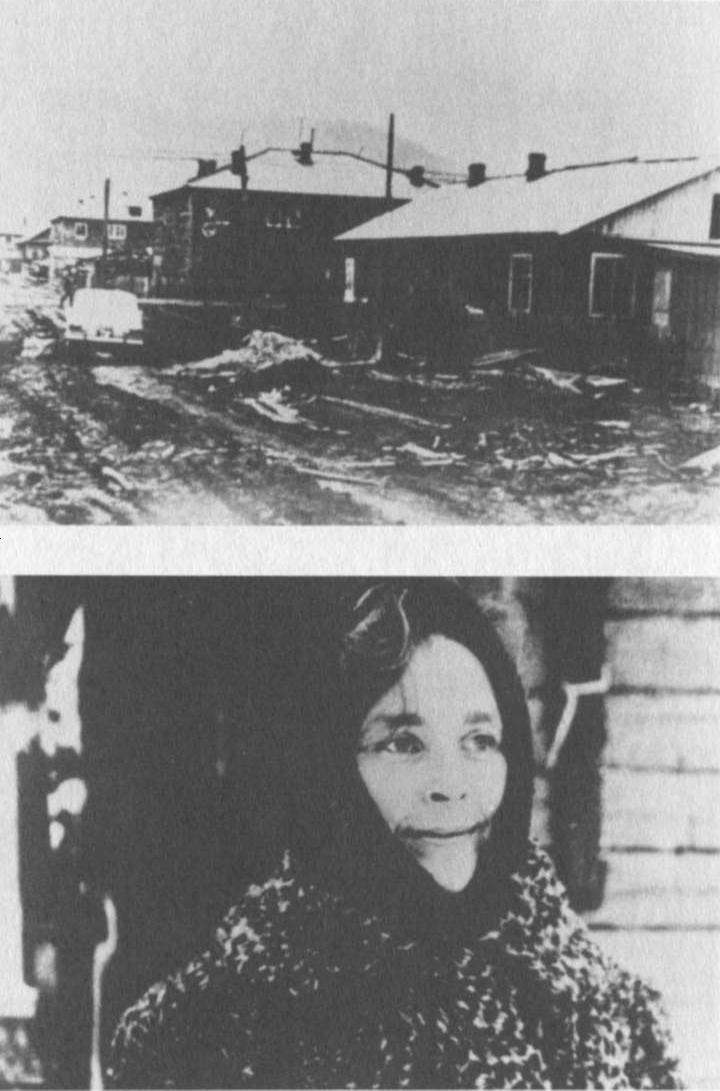

Home of Nijole Sadunaite in Vilnius (top); the "X" indicates the apartment from which she was arrested.

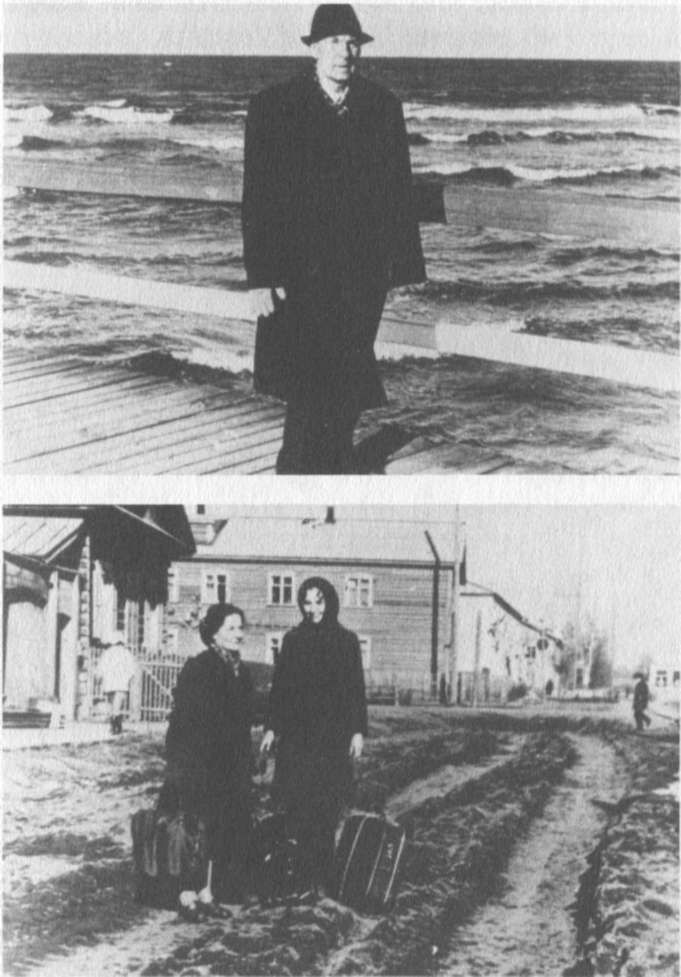

The desolate town of Boguchany, Siberia in 1977 (top), where Nijole Sadunaite spent three years in exile. Nijole is shown here in Boguchany during the same year.

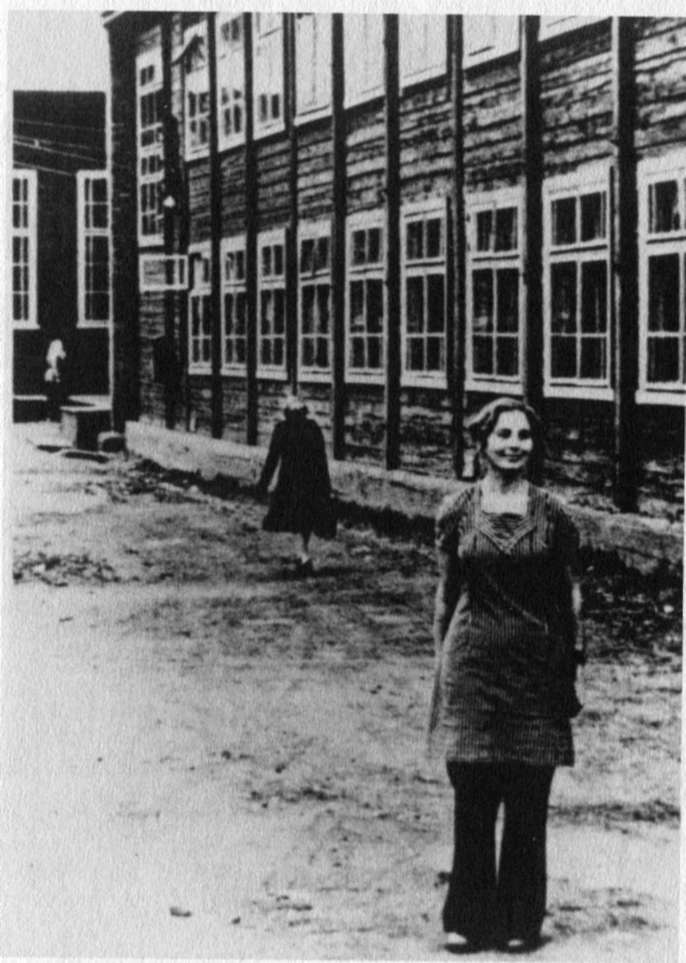

Nijole Sadunaite in Boguchany, Siberia during her exile in 1977.

Nijole Sadunaite and friends in the Siberian town of Boguchany during her exile in October 1977.

Nijole Sadunaite in Boguchany, Siberia "sitting in the yard writing letters and enjoying the fresh air" during her exile in 1979.

Nijole Sadunaite in the Spring of 1981 after her return to Lithuania from exile in Siberia.

Document which summarized the meeting expelling Nijole from her cooperative apartment (refer to Part III in the text "No Home and No Work: The Harassment Continues").

The man Nijole refers to as Lithuania's "heroic martyr," Petras Paulaitis (top), was well known as a member of the Lithuanian Underground. He is shown here after his return to Lithuania in October 1982 after 35 years of imprisonment in the Soviet Gulag. He died on February 19,1986. Nijole is shown with her best friend Brone Kibickaite on her arrival to Boguchany in 1977.

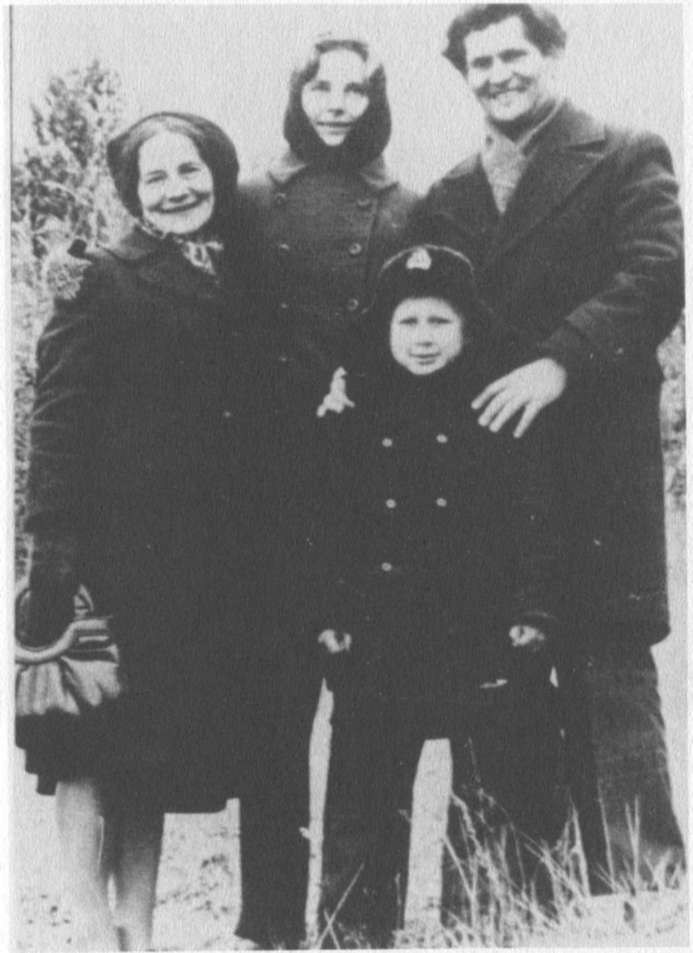

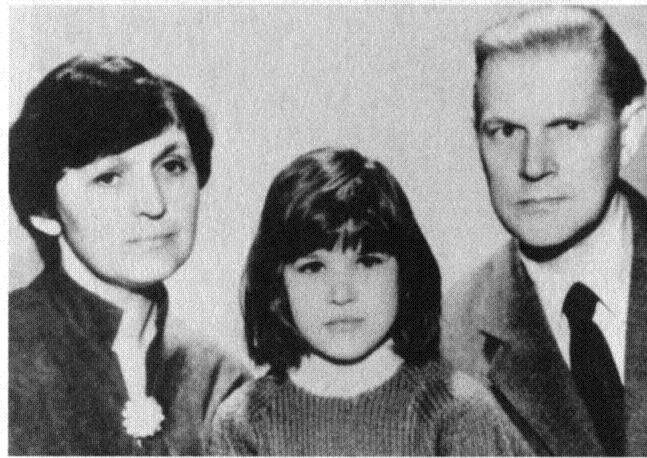

Jonas Sadunas, Nijole Sadunaite's brother, is shown here with his wife Maryte Saduniene and his daughter Marija Sadunaite in a photo taken on May 7,1983. Jonas was sentenced to one and a half years general regime labor camp at this time for fabricated charges of slander.

being transported behind bars, but the car is so full of blue smoke that you cannot see anything a few paces away.

Anyone unaccustomed to smoking becomes dizzy as though poisoned. At night it is cold, because they open little windows. Most of the prisoners are very lightly dressed and the nights are often damp and cold even during the summer, to say nothing of winter.

Male political prisoners are transported in the same pen with criminals, who ridicule them, take away everything, and moreover beat them up. The soldiers just incite them and laugh, since prisoners of conscience are called fascists by the Soviets—such a one should be beaten!

Criminal prisoners have sunk to such depths of amorality that being in the same car with them, you feel the greatest moral suffering, to say nothing about those whose lot it is to be with them in the concentration camps. This has lately become, in the Soviet Union, a daily occurrence. The chekists now warn everyone, "Well lock you up together with the criminals!" Or, "Well shut you up in a psychiatric hospital!", or, "Well hire murderers and theyll kill you tonight. And so there will be no trace of you left!"

On the way to the Female Political Prisoner Strict Regime Concentration Camp in Mordovia, I stayed four to six days in the jails of Pskov, Yaroslavl, Gorky, Ruzayev, and Potma—at transfer points. When, after a few days of travel, the soldiers would shove us out of the car, often kicking the weaker ones, and herd us into the "raven" which would take us to the jail, the "raven", covered in black sheet iron heated by the sun, and stuffed with prisoners, would be as hot as a furnace. People were suffocating. The thirst was agonizing. The limbs began to grow numb, for we were packed almost on top of one another—unable to move.

In a cubicle intended for one, they would lock me up with another female, and we would suffer together. The jails were also overcrowded. The cells held more than the allotted number of prisoners; hence it was necessary to wait and suffer almost a half-day in the "raven" until they would free a cell for the new arrivals.

They would let us out of the "raven" and into a common cell, from which, after a long delay, they summoned us, according to the paragraphs of the Criminal Code under which we had been sentenced, searched us, and assigned us to cells.

The jail cells are dismal, dirty and often full of a wide variety of parasites—bedbugs, fleas, lice, roaches—and in the little yards where they would take us a half-hour a day for exercise, there were rats.

In the cells, it is cold and damp, for no ray of sun gets in. In the windows are several rows of rusty bars. What is more, a perforated sheet of iron not only keeps the light from getting in, but even air. Hence in the cells the light burns day and night. At Pskov, they shut me up for a whole week in the jail's basement, in solitary. The ceiling of the cell was low, and the walls damp, with a concrete floor to which a rusty iron bed (without mattress) was fastened. Ushering me in, they issued an old, dirty and ragged blanket. Right in the cell was a hole in the floor for a toilet. The little window was sealed with sheet-iron, and the light burned all the time.

In the concentration camps and prisons, they feed you enough to keep you from starving: in the morning, in an iron bowl, are a few spoons of porridge, cooked from the lowest grade of groats, without any fat, and a cup of muddy water—tea. For lunch—a dipper of a thin concoction called ba-landa, and again, a few spoons of porridge, over which they poor some malodorous fat, or they give you a little piece of fish, from which the prisoners often get food poisoning. I, too, suffered food poisoning many times from that fare.

In the evening, once again, a few spoons of groats, and tea. They also give you half a little loaf of bread each day which, on account of its poor quality, I could not eat. For eating, they pass a karmushka through the opening of the door. It is strictly forbidden to speak to the prisoners distributing food. Often standing next to them are soldiers. All the prisoners are thin skeletons covered with pale, bluish skin. They often joke, "As long as the bones survive, the flesh will grow back."

When they took us from the jail, there would be another search, and again the "raven", the station, the iron bars in the railroad car; in my compartment now they would pack other female prisoners, and the journey continued.

Besides Pskov, we were temporarily incarcerated in the jails of Yaroslavl, Gorky, Ruzayev and Potma, where they would shut me up in the same cell with female criminals, including murderesses.

There were many female prisoners. I was with young fifteen-year old offenders sentenced for robbery and murder, with pregnant women, mature women and those who were quite old. I was amazed at the terrible amorality on the part of all of them, the complete loss of discernment between good and evil, the dehumanization. Here you see what a poor creature man is without God, and that the greatest offenders of all are those who systematically, forcibly and constantly infect everyone with the atheistic lie—the Soviet Government atheists. Those millions of poor dehumanized prisoners are the fruit of their "education".

Finally, they brought me to the last jail, in Potma, where they shut me up with female prisoners in a large cell. Instead of beds, as in the Gorky jail, we slept on slightly raised wooden pallets. We were attacked by bedbugs in such numbers that we began protesting. The guards told us that there were no bedbugs in the cell. Then we caught a few of them and, writing a protest to the warden, we included the bedbugs as evidence. After a half-day, they took us to another cell where there were fewer parasites.

In the prison yard and toilets, light brown rats roamed impudently (until then, I had seen only grey rats). After a few days, they herded us all into a train, but they did not put me in the same car with the female criminals. They told us that they had to transport "specially dangerous state criminals", namely me, in a separate compartment, under special guard. They shut me up alone in a double compartment.

The Potma prison guards were surprised that I did not know how to curse or swear. "Where did you come from?" they asked, "By the time they transport you from camp to exile, you will have learned everything." To their greatest surprise, their prophesy was not fulfilled—during my transport from camp to exile, I came to meet some of the guards again. I finally reached my last transfer point.

They shut me up in a separate cubicle in the railroad car and took me away. From Potma, a narrow-guage train transported the prisoners through swampy forests. Along the whole route, the only things we could see through the little open windows were barbed wire enclosures—concentration camps— soldiers, guards and dogs, one after the other, more than twenty concentration camps in which were crowded a whole Soviet republic of slaves. The hard-labor concentration camp for female political prisoners is reached after passing all the other concentration camps strung out along the railroad line, which carries prisoners almost exclusively. For this reason, they did not even close the little windows here. We had arrived in a slave state.

Finally we were at the last stop and they ordered us out. They sent various individuals to different places; I was herded into the reception room of the women's concentration camp, where I was searched. They took my copy of the court's decision for "verification", and they never returned it, even though I appealed to the concentration camp commandment many times in writing, asking him to return it. Soviet officials do not like to leave the decisions of their criminal trials with political prisoners, and they seize them from almost everyone soon after the trial, or after transport to camp. After the search, they put my clothing in storage, and clothed me in prison garb.

The journey from Vilnius to Mordovia had taken a whole month.13 The female prisoners greeted us with love and concern, and one Ukrainian prisoner gave me a pleasant surprise by laying out before my plate little flowers arranged in the form of the tricolor of independent Lithuania.

The women's concentration camp zone was small—a tiny triangular yard surrounded by a double fence of barbed wire and a third high fence of wood, so that one might not see anything. On top of this was a guardhouse. It was strictly forbidden for the prisoners to speak with guards.

13During the long and exhausting trip to Mordovia, Nijole lost thirty-three pounds. Camp food is very monotonous and of poor quality: barley mash without any fat, fish, left-over scraps of meat (cow udder, diaphragm, lungs). In the fall, cabbage soup is served for several months, but when the cabbage supply runs out, another kind of soup is made for several months, but always the same soup. Nijole fell ill on October 10, 1975, suffering from fever and dizziness throughout the Winter and on into the Spring of 1976. She was ill again the following Winter.

In the center of the yard was a little old wooden house, or barrack, in which one room served as a dormitory, another as dining hall and next to it was the workroom where each prisoner was required to sew sixty pairs of work gloves a day. Anyone failing to fill her quota was taken to the punishment cell. The sewing machines were ancient, and would often break down. The thread was of poor quality and would snap every few minutes—sheer torture. I used to sew my quota from 6:00 AM to 11:00 PM with brief breaks for eating, exercise and prayer.14

14Nijole's sufferings and strength of character are described more thoroughly in a letter written by her during this time: ". . . And how good it is that the small boat of our life is steered by the hand of a good Father. When He is at the wheel—nothing is frightening. Then, no matter how hard life becomes, you will know how to fight and how to love. And I can say that the year 1975 has flown by like the wink of an eye, but it has been my joy. I thank the good God for it "

"On March 3, I returned from the hospital. At last it looks as though I will be up and about, Your diagnosis was quite accurate—acute exhaustion.