On September 24, 1983, Engineer Vytautas Vaičiūnas was released from Bakal Labor Camp, after serving his sentence. At the camp, the revered prisoner was met by his brother and by youth who had come from Lithuania. When he arrived back in the land of his fathers, he was warmly greeted by young people and his friends. Engineer Vaičiūnas returned tired but strong of spirit. It had been a general regime camp. On account of unsanitary conditions and hoardes of parasites, there had been repeated epidemics of dysentery which the engineer barely survived.

Presently Vytautas Vaičiūnas is living in Kaunas.

On July 27, 1983, Anastazas Janulis was taken by transport from the camp in Barashevo to the transfer point in Perm, from where he was allowed to return to Lithuania, July 29, once his documents had been put in order. Upon his return to Lithuania, Janulis took lodgings at the abovementioned address in Kaišiadorys.

On August 2, when he went to the Kaišiadorys Passport Section to register, the official at the pasport desk, apparently informed

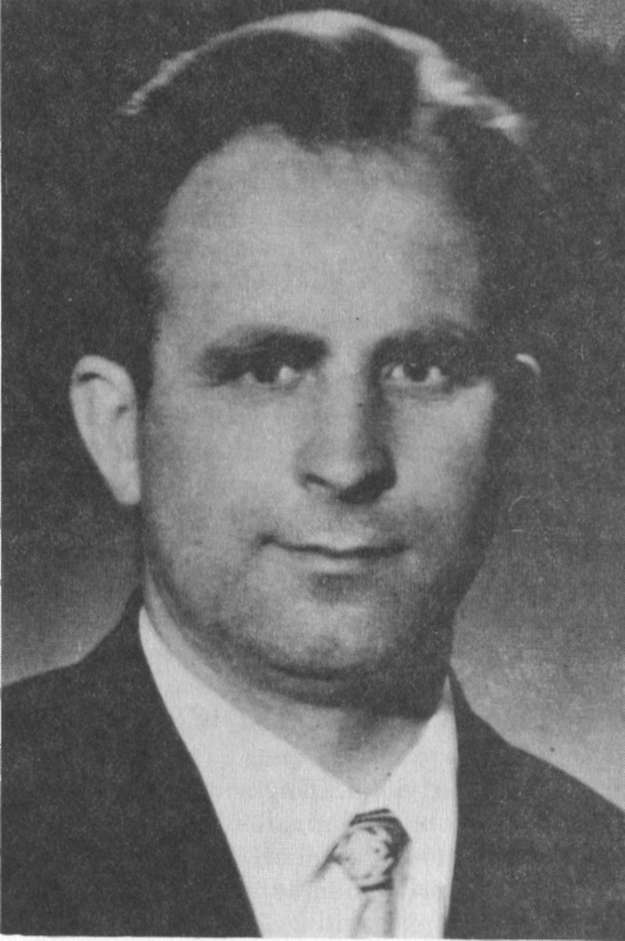

Vytautas Vaičiūnas

in advance about the impending visit of Janulis, sent him to the director, and she sent him to the Office of the Chief Inspector of Criminal Investigation. After he had taken care of his papers, the chief inspector openly stated that Janulis would be watched, and he gave him to understand that it depended on his own behavior, whether he would be assigned an administrative overseer.

After his conversation with the inspector, Janulis was summoned by the chief of the KGB; in the office with him was another chekist. To the repeated question whether he would engage in further underground work, Janulis replied that not only during the

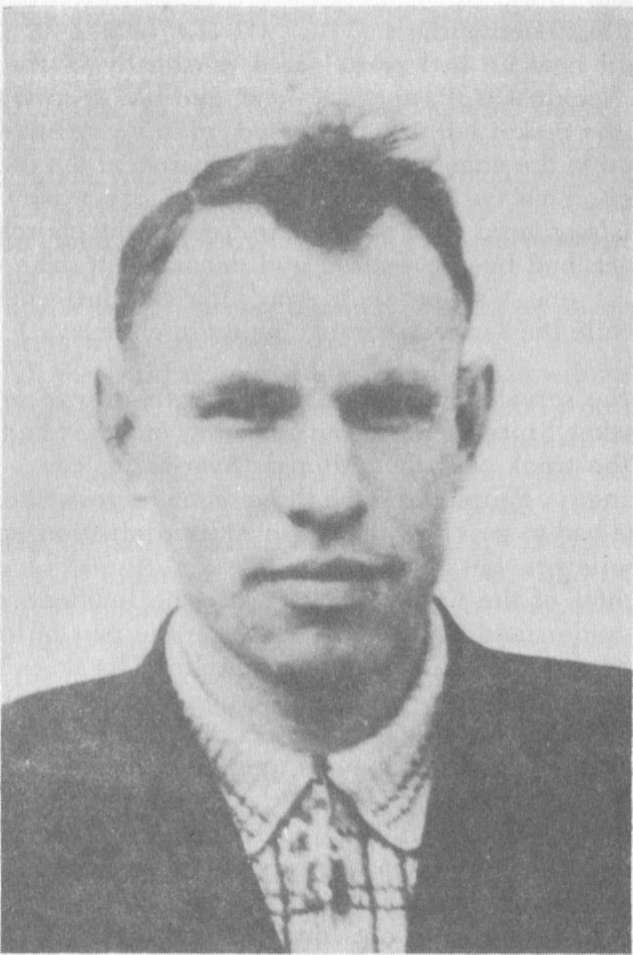

Anastazas Janulis

interrogation, but during the trial, he had answered this question, saying that he would always act according to his conscience and his convictions; today he could repeat the same thing, after having returned from camp.

The chief of the KGB wanted to convince Janulis that those responsible for poor relations between the state and the Church were the extremist priests; he tried to accuse Father Alfonsas Svarinskas and Father Sigitas Tamkevičius of preaching anti-Soviet sermons. To the attempt to call the Chronicle and other underground publications libelous, Janulis submitted a whole list of specific facts of which he himself had been witness.

He told how he had participated personally in the funeral of Father Z. Neciunskas, Pastor of Kalviai, and had seen with his own eyes how the casket with the deceased priest's remains was driven from Kalviai to the cemetery of the home parish of the deceased. On orders from officials of the Kaišiadorys Rayon Executive Committee, local officials ordered from the park in front of the churchyard three trucks which had been prepared and decorated to take the casket. (As soon as one was ordered away, the faithful would arrange another, while the services were going on in church . . .)

After the services, it became clear that there was no vehicle to take the casket. Since there was no other way out, they had to take the casket in the trunk of Father Alfonsas Svarinskas' car. . . The sight was shocking . . . People from the three rayons across whose territory the cortege had to pass saw the obvious discrimination, scandalizing not only believers, but everyone.

The chief of the KGB tried to justify he incident, calling it a minor misunderstanding, excessive zeal on the part of local organs, and claimed that someone had been disciplined for it. . . Toward the end of the conversation, the chekist tried to show that Lithuania has attained much during the Soviet era, that enough religious literature is published for the believers, etc., and that people are happy with their free union with the USSR.

Janulis recalled that in this area, too, he is a living witness, that he had seen how the ballot was carried out in those days, and he recalled the deportations . . .

Seeing that they were not communicating, the KGB man asked how Janulis looked on articles published in the press about those who had been sentenced, e.g., Father Alfonsas Svarinskas. Janulis replied that he considered articles about others as he did an article about himself after his sentencing — that is, as a crude distortion of the facts, an effort to vilify and to denégrate with falsehoods things that never happened.

As they were parting, the KGB expressed the hope that this conversation would not be their last. Janulis on his part expressed the hope that he would not have to fight with them about unnecessary summonses.