(The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania)

1. SITUATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN LITHUANIA IN SOVIET TIMES

After the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact by the USSR and Germany on 23 August 1939, Lithuania was assigned to the Soviet sphere of influence and was occupied on 15 June 1940. The USSR, however, did not want to have an official occupational status, and, thus, organized the farce of elections to the Liaudies Seimas (People's parliament) on 14-15 July 1940. During its first session on 21 July 'the elected' Seimas declared Soviet rule in Lithuania and decided to ask for Lithuania's admission into the Soviet Union. On 3 August the delegation of the Seimas brought 'the sun of Stalin' to Lithuania from the session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in Moscow. After registering officially "the voluntary entry of Lithuania into the USSR" on the basis of a juridical farce, the occupants could begin fulfilling more openly and boldly their political, economic, and social goals - to sovietize all spheres of Lithuania's life as quickly as possible according to the USSR model.

The restrictions of the rights and activities of the Church began immediately after the occupation: the decree on separating the Church from state and school was promulgated already on 25 June 1940. Religious classes in schools were abolished; chaplains were expelled from the army, schools, and prisons; the faculty of the Theology-philosophy Department of the University of Vytautas the Great in Kaunas was abolished; all Catholic institutions of teaching and care were closed; religious press was forbidden; mandatory civil registration of marriages was established. On 5 August all the land belonging to the Church was nationalized and at the end of October also all the buildings. The Concordat with the Holy See was broken off.1

Although the leaders of Lithuania's Catholic Church tried to find a modus vivendi in the new occupational conditions, the ever growing restrictions on the activities of the Church and its protests against them made it clear that it would be impossible to reconcile the Communist

-------------

1 Arunas Streikus, "Lietuvos Katalikų Bažnyčia 1940-1990," [The Catholic Church in Lithuania 1940-1990], LKMA metrastis [LKMA Chronicle], XII, pp. 39, 40.

authorities and the Church. The Communist authorities were forced to fight against Lithuania's Catholic Church not only for ideological but also for political reasons: they viewed the Church as the main ideological force and leader of the Lithuanian nation not to yield to the occupation and annexation.

In order to break the influence of the Church on the population, the repressive authorities, as was usual in the Soviet Union, began working. Already on 2 October 1940 Secretary of the NKVD* of the LSSR Petr Gladkov ordered all the chairmen of district departments to enter all priests into the strategic register, i.e. to begin observation cases against them.

During the first occupation (in 1940-1941) the Soviet authorities did not hurry to repress many priests. However, during the year until the beginning of the war between Germany and the USSR in Lithuania (including the Lithuanian part of Vilnius diocese) 39 priests were arrested and imprisoned, and 21 priests tortured to death or killed when the Soviet army was retreating from Lithuania.2

With Germany's defeat in the war and the return of the Soviet army in 1944 to Lithuania, many inhabitants of Lithuania repatriated to Poland, Germany, and other Western countries because of the threatening terror, war conditions, or forced by the German army. Until 1958 their number was calculated to be 490 thousand.3 Among them were three bishops -Kaunas Archbishop Metropolitan Juozapas Skvireckas, his assistant Bishop Vincentas Brizgys, and the assistant Bishop of Vilkaviškis Vincentas Padolskis - who went to the West and Archbishop Romuald Jalbrzykowski who was deported to Poland by the Soviets (in 1945). About 300 priests withdrew to the West. There were 1,579 priests** in Lithuania in 1940 and 1,232 in 1945. So during the first five years of occupation and war Lithuania lost 347 priests, i.e. around 22 percent. Until the middle of 1947 (until the arrest of Archbishop Mecislovas Reinys) 110 priests repatriated to Poland from the Vilnius archdiocese. Thus even without counting any repressions until 1948 about 460 (29 percent) priests who had worked in 1940 had been lost.4

Although it had lost a great part of the more initiative and active priests, at the beginning of the second Soviet occupation the Catholic

--------------------

* NKVD (Narodnyi komisariat vnutrennich del) - National Commissariat of Internal Affairs.

2 Vytautas S. Vardys, ed. Krikščionybe Lietuvoje [Christianity in Lithuania], Chicago, 1997, p. 375.

3 Arvydas Anušauskas, Lietuviu tautos sovietinis naikinimas 1940-1958 m. [The Soviet Annihilation of the Lithuanian Nation in 1940-1958], Vilnius, 1996, p. 404.

** According to church Elenchus there were 1,339 priests in the provinces of the Lithuanian Church in 1940 and 173 priests in the Lithuanian part of the Vilnius diocese (1939). So there must have been no less than 1,512 priests in 1940. There may have been even 1,579 priests.

Church did not lack bishops and priests: except for the Kaunas archdiocese, the other 5 dioceses had their own bishops (the Vilnius and Telšiai dioceses even had 2 bishops each) and as mentioned earlier there were 1,232 priests at the beginning of 1945.5

After the return of the Soviet army the immediate tasks of the occupational authorities remained the same as they had been in the years of the first occupation (in 1940-1941): to sovietize all spheres of life and to strengthen its rule. However, at that time the war was still continuing in Germany and this took its toll: the occupational authorities declared a mobilization. The men of Lithuania did not obey the unlawful demands of the occupants: they began to hide and withdrew to the forests. The Soviet authorities began very cruel repressions: the NKVD army not only 'cleaned' the forests and caught those hiding, but often shot them even if they were unarmed. This cruelty of the occupants convinced many men to arm and to unite into groups. While the war was still continuing, at the end of 1944 partisan groups functioned in almost all the districts of Lithuania and in the spring of 1945 there were about 30 thousand partisans in the forests.6

The Catholic Church in Lithuania could not stay completely aloof from this fight which was marked with the customary brutality and inhumanity of Communist regimes: even the bodies of killed partisans were mutilated in the streets of small towns and later the bodies were thrown into rubbish-heaps, gravel pits or drowned in wells or toilets. During the first post-war decade more than 20 thousand partisans (both men and women) were killed in this unequal fight in Lithuania, 40 thousand people were imprisoned in gulags*, 132 thousand inhabitants were exiled to Siberia and other regions of inclement climate in the Soviet Union. Lithuania lost 1.06 million inhabitants, i.e. more than one third of its population, because of the war, the withdrawal from Lithuania, the terror executed by the occupants, and other reasons in 1941-1958.7

In order to implement the policy of the Soviet authorities toward religions in the Soviet Union, while the war was still continuing (in 1943-1944) the Council of Religious Affairs (hence - RKRT)** at the

-------------------

4 The calculation was made on the basis of Lietuvos centrinis valstyhes archyvas [Central State Archive of Lithuania] (LCVA). F.R-181, Case of doc. 3, f. 65, sheets 1-50; F. 22, sh. 53-70 and Lietuvos ypatingasis archyvas [Special Archive of Lithuania] (LYA). The documents of criminal case No. P-14999-LI, sh. 67-70.

5 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 22, sh. 53-70.

6 Nijole Gaškaitė, Pasipriešinimo istorija 1944-1953 metai, [History of Resistance. The years 1944-1953], Vilnius 1997, pp. 36-38.

* Gulag (Glavnoe upravlenie lagerei) - The head department of camps. It was a section of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR which was in charge of prisons, camps, and places of exile.

7 Anušauskas, pp. 403, 404.

** Later it was named the Council for Religions Affairs (RRT)

Council of People's Commissars of the USSR was established. Although its official purpose was to monitor and regulate the relations between all religious institutions existing in the USSR and the state as well as to ensure that the laws concerning the cults were observed, this council and its representatives in the republics were actually the coordinators of the struggle against confessional institutions (even sometimes using them) as well as the creators of the methods and the executors of the measures used in this struggle. The main repressive structure of the USSR - the KGB* - was as active as the council in this (they collaborated tightly although sometimes as rivals). The strategist of anti-religious policy and the approver of all more or less important methods and measures was the Communist Party, i.e. the Central Committees of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and of its republics.

During the whole period of the Soviet occupation (1940-1990) the Lithuanian Communist Party had two goals regarding the Church: 1) to destroy it, 2) while it existed to use it when it was deemed useful for the internal and foreign policy of the USSR. The institution of the representative of RKRT was officially established in Lithuania on 22 December 1944. During the time of occupation, this institution collaborated tightly with the KGB (NKGB, MGB) in fighting against the Church.

Teaching of religion. Immediately after Soviet power was re-established in 1944, chaplains were expelled from the schools again. In order to avoid the great dissatisfaction of the believers it was permitted to teach pupils religion in churches, but this was forbidden after 1946. It was only allowed to catechize children (to prepare them for the sacraments of Confession and First Communion) during the summer school vacation. However, from 1947 it was forbidden to catechize children. Moscow (RKRT Chairman Igor Polianskii) viewed this as a too extreme measure and decided "not to take strict measures for a while and to leave the present practice regarding the catechization of children."8

However, the republic authorities (LKP(b) CK**, the Council of Ministers, and the MGB) restored the ban in 1948 and left the right to catechize children only to their parents: a priest could only individually check the knowledge of a child.

Press. Just as during the first occupation, after Soviet power returned, the publication of any religious literature was forbidden, and the

-------------------

* KGB (Komitet gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti) - The Committee for State Security. Until 1946 this institution was called NKGB - People's Commissariat for State Security, in 1946-1953 the MGB - The Ministry for State Security, and since 1954 - KGB.

8 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 10, sh. 40.

** LKP(b) CK - The Central Committee of Lithuanian Communist (Bolshevik) Party.

Catholic printing houses were taken away. Religious literature (deemed to be nationalist and fascist) was removed not only from public libraries but also from the libraries of the seminaries and churches and destroyed. (A part was transferred to the special funds of state libraries). A few years after the end of the war the believers lacked elementary books, such as catechisms, prayer-books, and the priests lacked liturgical books.

Religious organizations. The destruction of religious organizations was carried out with particular zeal. Before the war several Catholic youth organizations were active in Lithuania: Ateitininkai for schoolchildren and students,Pavasarininkai for youth from the countryside, and Angelaiciai (Angelo sargo) for children. There were many organizations for prayer, charity, and cultural activity, such as The Live Rosary, Tretininkai, Vincent de Paul Society, St. Zita Society, the Catholic Activity Center. All Catholic organizations were forbidden and liquidated by the Soviet authorities.

Monasteries. In 1939 there were 42 monasteries and cloisters with more than 1,500 monks and nuns in Lithuania (including the Vilnius region).9 On 3 January 1947 the representative of the RKRT suggested to the LKP(b) CK and the Council of Ministers that the Jesuit, Marian Fathers, Franciscan, Salesian monasteries be liquidated and their closing began the same year. In 1947-1948 all the monasteries were closed. In order to bar monks who were priests from priestly activity all the churches belonging to monasteries were closed, and in the 1948/1949 school year all the teachers and students belonging to the monastery orders were expelled from the Kaunas theological seminary. In order to get an appointment as an official diocesan priest, monk-priests had to write applications to the administrators of the dioceses. The authorities hypocritically explained this forced step as their voluntary resignation from the monasteries. Allegedly, they no longer desired to remain monks, after the monastic orders lost their land and wealth. The representative of the RKRT called this destruction of the monastic orders as the 'natural self-elimination of the monasteries'.

Theological seminaries. From the very first days of the occupation special attention was directed to the theological seminaries. In 1940 there were four theological seminaries in Lithuania: in Vilnius, Kaunas, Telšiai, and Vilkaviškis. By decision No. 53 of the Council of People's Commissars of the LSSR, dated 9 February 1945, only the Kaunas Theological Seminary remained open. There were 318 theological students in the seminary in Kaunas during the school year of 1945/1946.10 The buildings of the seminary were occupied by soldiers, and the theological

-----------------

9 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 35, sh. 86, 87; Regina Laukaitytė, Lietuvos vienuolijos: XX a. istorijos bruozai [Monasteries of Lithuania: Features of Their History in the XXth Century], Vilnius, 1997, p. 89.

10 ibid. F. 9, sh. 27-35.

students were forced to look for shelter in the still functioning monasteries of the Jesuits and Marian Fathers, or in the city.

The church leaders repeatedly requested that the authorities return the buildings, but the latter 'found' another solution: they reduced to 150 the number of students allowed to study in the seminary in the 1946/1947 school year, expelling the rest. In 1949 the leader of Lithuanian Communist Party - LKP(b) CK First Secretary Antanas Sniečkus suggested closing the last seminary, but it was decided to cut the number of students in half to 75. The last reduction - down to 30 students - was made in 1961. After that time only 5-6 students were admitted to the first course each year.

In addition to setting limits on the number of students allowed to study in the seminary, the authorities also rudely interfered in the selection of the students as well as of the leaders and teachers of the seminary. In the post-war years (1945-1953) the rector of the seminary, several teachers, and more than ten students were arrested and sentenced, some of them exiled to Siberia. The candidates who were not approved by the representative of the RKRT (in fact by the KGB) could not enter the seminary. The KGB tried to recruit the students (and teachers) by blackmailing them: the KGB made them collaborate, broke their conscience, and interfered with their spiritual education. If in the post-war years such students comprised only 1-3 percent of all the students, then at the beginning of the 1980s they comprised about 20 percent. However, according to the testimony given by the KGB officers, only half of the recruited students collaborated willingly while the others gave no reply or made various excuses, and after they graduated from the seminary some firmly refused to collaborate. This induced the leaders of the KGB of the LSSR to issue in 1988 order No. 6s which obligated the chairmen of all its departments to send "screened agents selected from the non-believing and patriotically disposed youth" to study at the theological seminary. The meddling of the representative of the RKRT and the KGB into the selection of students (some of the young men even tried to enter the seminary 7-10 times) led to the establishment of an underground theological seminary in Lithuania in 1971 in which some of the rejected students and those who had no chance of getting through this 'sieve' could prepare for priesthood. This seminary prepared more than 30 priests for Lithuania (and also for Belarus and Ukraine). Two of them were later ordained bishops: Apostolic Administrator of Kazakhstan and Central Asia John Paul Lenga and Telšiai Bishop Jonas Boruta.11

----------

11 Academician Bishop Jonas Boruta, Algimantas Katilius, "Pogrindine kunigų seminarija." [The Underground Theological Seminary], LKMA metraštis [LKMA Chronicle], XII, pp. 217-219.

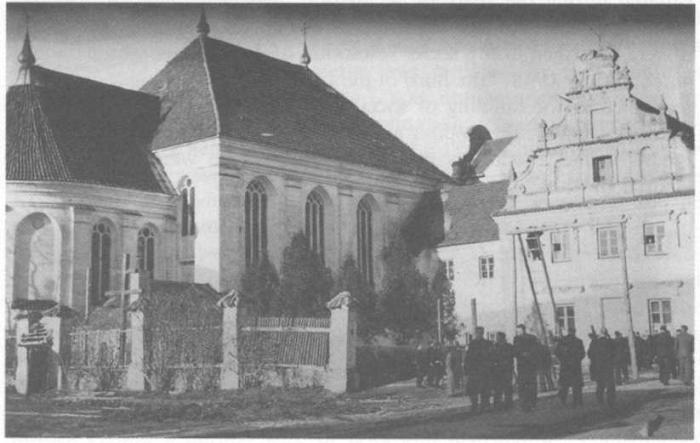

Closure of Churches. Reducing the number of churches was an important part of the authorities' plans to destroy the Church physically. In the beginning of 1940, there were 732 Catholic churches in Lithuania, and 711 were left in 1945. The pretext to close the churches and to leave priests 'unemployed' was provided by the special top-secret instruction No. 75 received from the RKRT under the LKT* of the USSR (in Moscow) in February 1945. It required in six months the establishment of executive committees ('dvadtsatka' in Russian - the twenties) in all religious communities, which were to manage all the activities of the community (parish) and make the priest only its "hired servant of the cult," and the registration of these communities and priests.12 This demand, in essence, contradicted the canons of the Church.

The RKRT (in Moscow) made plans to join the Catholic Church in Lithuania to the Russian Orthodox Church, but fearing the mass opposition of the believers and the possible intensification of the partisan fight, both the representative of the RKRT in Lithuania and even the leader of the Lithuanian Communist Party Sniečkus opposed this idea. The registration of churches began in 1948. The registration was a very good opportunity to close churches and to get rid of undesirable ('disloyal') priests.

First, the churches and chapels of liquidated monasteries were closed. In 1948 in Vilnius only 10 churches were left whereas 30 were closed. Kaunas was left with 12 churches.13 The representative of the RKRT at one time even considered leaving only one church in each district.14 The closing of churches was carried out until 1966. In 1949 the Vilnius cathedral was closed because 'the believers did not attend it15.

The construction of new churches was not allowed. During the whole period only two new churches were built (in Klaipeda and in Švenčioneliai), and the former was taken away from the believers even before it was opened. If there were more than 870 churches and chapels in Lithuania (including the Vilnius diocese) in 194015 then in 1951 only 670 were open.16 Until 1966 40 more churches were closed and only 630 functioning churches remained.17 Subsequently, churches were no longer closed. Thus, during the whole period of occupation (1940-1990)

------------

* LKT - The Council of People's Commissars (later renamed the Council of Ministers).

12 LCVA. F.K-181, C. d. 3, f. 4, sh. 4.

13 ibid. F. 13, sh. 29; F. 15, sh. 52.

14 ibid. F. 13, sh. 80.

15 Calculations made from Elenchus omnium ecclesiarum et universi cleri provinciae ecclesiasticae Lituanae pro anno Domini 1940 and Catalogus ecclesiarum et cleri archidioecesis Vilnensis pro anno Domini 1939. From the personal archive of Rev. Vaclovas Aliulis MIC.

16 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 25, sh. 133-135.

17 ibid. F. 116, sh. 1-15.

240 churches and chapels were closed, i.e. 27.6 percent. The closed churches were burglarized and devastated (most of the time turned into warehouses).

The Annihilation of the Living Church. As mentioned earlier, the Soviet authorities considered totally abolishing the Catholic Church in Lithuania by joining it to the Russian Orthodox Church. Another suggestion was to separate it from the Universal (Catholic) Church. For this reason, as in many other Communist countries, they tried more than once to separate the Church in Lithuania from the Vatican in 1945-1951 and to establish a so-called national church. This was to be carried out by priests, ensnared by the MGB, who were to organize first a statement of the priests, and later a congress which would declare its separation. Due to the position of the absolute majority of the priests of the Catholic Church in Lithuania the effort to establish a national church failed.18

After the death of Stalin (in 1953), all efforts turned not to the juridical, but to the actual separation of the Church from the Vatican by infiltrating deeper into the Church's internal life and rule. From the very beginning of the second occupation the Soviet authorities undertook active measures to force the bishops to obey them. The Soviet authorities (usually the MGB) with deceit and violence tried to make them collaborate: to make them MGB agents and "to reorient Lithuania's Catholic clergy into positions loyal to the Soviet authorities".

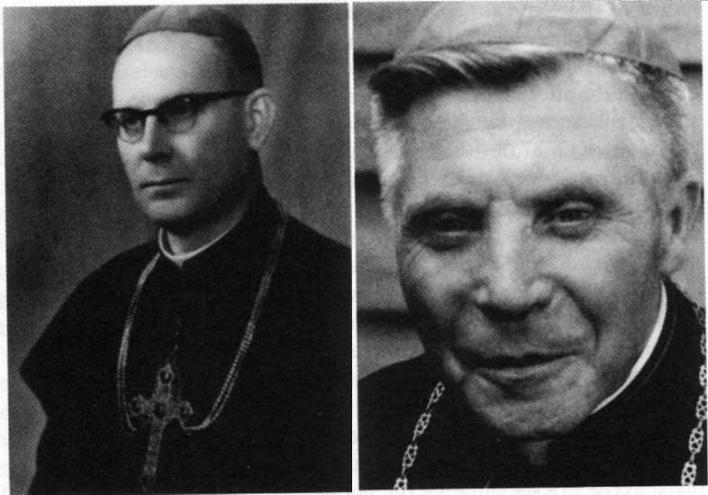

The efforts of the KGB to put their people into the posts of the administrators of the dioceses continued during the whole period of occupation. Only a priest who was acceptable to the representative of the RKRT and the KGB could be appointed as the administrator of the diocese. The legal administrators of the dioceses - Bishops Teofilis Matulionis and Pranciškus Ramanauskas both of whom had returned from prison and Bishops Julijonas Steponavičius and Vincentas Sladkevičius who had not made concessions to the authorities - were not allowed to rule the diocese to which they had been appointed and were even exiled from them.

In order to lessen the influence of the Church on society the authorities devoted special attention to splitting and provoking conflicts between the priests, especially the hierarchs. The representative of the RKRT and the KGB were involved in this work. The unity of the hierarchs was especially feared. After returning from exile, Bishops Matulionis and Ramanauskas tried to unite the hierarchs. Thus, plans were again made for their arrest or exile from Lithuania.

The words of the representative of the RKRT (1957-1973) Justas Rugienis eloquently describe the policy of the Soviet authorities in this

--------------

18 ibid. F. 17, sh. 23, 24; F. 18, sh. 27, 28; F. 19, sh. 6; F. 21, sh. 16, 139-144. LYA. F. K-l, C. d. 14, f. 73, sh. 1-16; F. 81, sh. 163, 164.

sphere: "In our everyday work with the clergy we have to continue splitting and creating conflicts among the servants of the cult. We have to try to appoint priests loyal to our order to the leading posts in the dioceses, such as administrators, chancellors, deans, or to give them the best parishes. And on the other hand, we must send reactionary priests who break Soviet laws to distant and small parishes through the hands of the administrators of the dioceses (underlined by the author)".19

Evangelical Activity. In order to lessen the influence of the Church on society the authorities directed special attention to restricting its evangelical activity. The ban on teaching religion to children and youth has already been mentioned. In 1947 it was forbidden to administer the sacraments to the sick in a hospital without the permission of its head physician. In 1949 it was officially forbidden to organize meetings of priests and capitulas of dioceses without the permission of the representative of the RKRT. Among the prohibited activities were: processions in the churchyard; the visiting of parishioners; inviting other priests to Church festivals and celebrations without the permission of the local authorities; the organization of choirs and their rehearsals at the church. It was forbidden for boys less than 16 years old to serve as altar boys during Masses and for girls to strew flowers and to participate in processions; to organize pilgrimages to places of worship, such as the Hill of Crosses, Šiluva, Žemaicių Kalvarija, etc. Priests were forbidden to spend time with youth and especially to organize events for them.20 The authorities wanted to isolate the priests from society as much as possible and to make them only the servants of the cult.

Repressions. In fighting against the Church the Soviet authorities used their usual measure - repressions, especially in the post-war years until the death of Stalin.

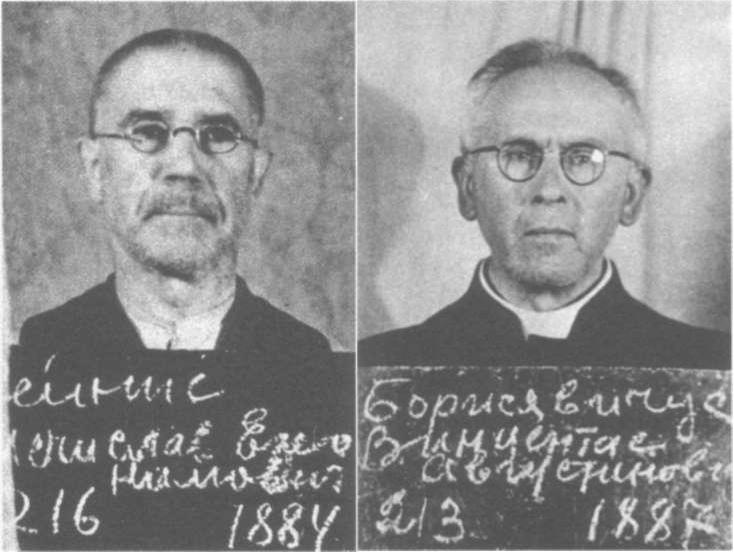

From the very first days of the second occupation strategic register (observation) cases were renewed or begun against all the bishops and priests: all priests were considered to be potential enemies. After selecting a priest, they, first, tried to recruit him as an agent and if this did not work he was often arrested. They detained Archbishop Mečislovas Reinys for two days in the NKGB prison (Gedimino pr. 40, Vilnius) already in September 1944 and tried to recruit him. In December 1945 Telsiai Bishop Vincentas Borisevičius was kept in NKGB cellars for one week and they also tried to recruit him. Bishop Kazimieras Paltarokas also did not escape recruiting attempts. (It seems that they did not try to recruit only Vilkaviškis Bishop Antanas Karosas who had recently celebrated his 90th birthday and Kaišiadoriai Bishop Teofilis Matulionis who had twice experienced Soviet prisons and gulags).

---------------

19 LCVA. F.R-525, C. d. 1, f. 45, sh. 26.

20 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 14, sh. 35-38.

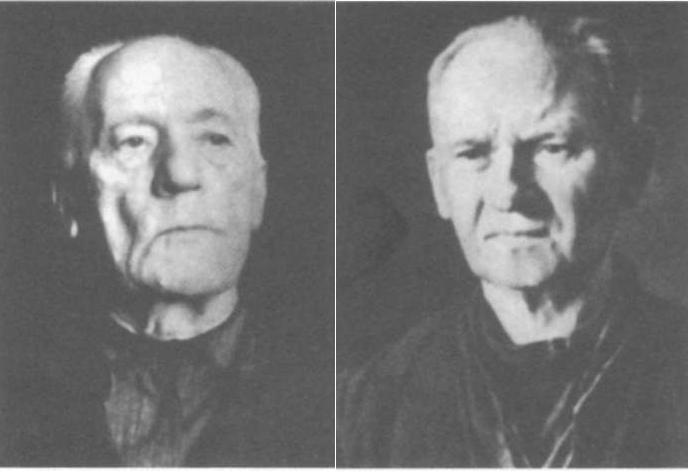

The first of the hierarchs of Lithuania's Catholic Church to be arrested was Bishop Borisevičius - on 5 February 1946. He was sentenced to death the same year and on the 18 November he was executed in Vilnius (together with Rev. Pranas Gustaitis). His real 'fault' was in refusing to collaborate with the NKGB. On 18 December 1946 Bishops Teofilis Matulionis and Pranciškus Ramanauskas were arrested and the following year they were sentenced to seven and ten years in prison, respectively. On 12 June 1947 Archbishop Mecišlovas Reinys was arrested and sentenced to 8 years imprisonment. (He died in the famous Vladimir prison in Russia in 1953). The only bishop who remained in Lithuania was Bishop Kazimieras Paltarokas. (Bishop Karosas died in 1947)

The most intensive years of repressions were the time of Stalin's rule. In the period 1944-1953 362 priests were repressed. The repressions against priests were carried out in this way throughout the years:21

Table 1

Year 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952

Number of

priests arrested 5 58 57 41 22 91 60 17 6

Because of the repressions Lithuania lost 29 percent of the priests it had in 1945. Only 672 open churches and 731 priests remained in Lithuania in 1953.22 Thus, during the mentioned period (1945-1953) because of repressions, repatriation, and deaths Lithuania lost 500 priests, i.e. 40 percent of the priests in 1945. The loss of the Catholic Church in Lithuania becomes even more eloquent if one counts from the beginning of the occupation in 1940: during the period 1940-1953 Lithuania lost 848 priests (only 731 out of 1,579 remained), i.e. more than half (54 percent). In comparison to the loss of the population (more than one third of the population) the loss of the Church was even greater.

After the death of Stalin (1953) the regime of the Soviet Union grew milder: the prisoners who had remained alive began returning from the gulags and exile. By 1960, 247 priests and two bishops returned.23 There were 924 priests in Lithuania in 1958.24 According to a report of the chairman of the RKRT, the priests who returned from the gulags comprised 30 percent of the priests in Lithuania and Latvia, 45 percent in Belarus, and even 80 percent in Ukraine.25

--------------

21 Streikus, p. 50.

22 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 36, sh. 60-86.

23 ibid. F. 58, sh. 27, 28.

24 ibid. F. 50, sh. 35.

25 ibid. F. 56, sh. 103.

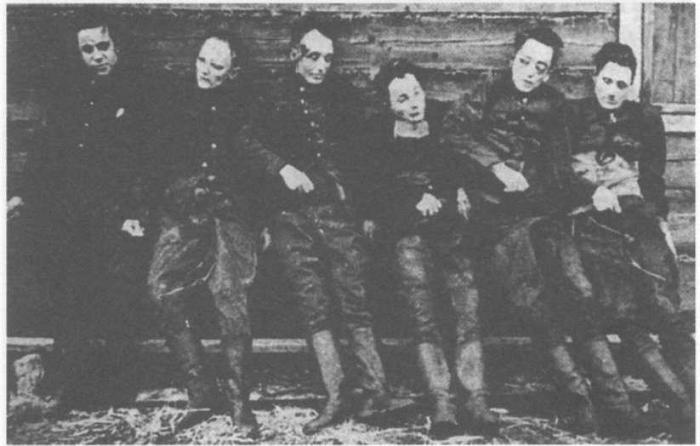

Meeting of partisan leaders of the Dainava district. 1948.

Mutilated bodies of killed partisans in the yard of the Lazdijai MGB in 1951.

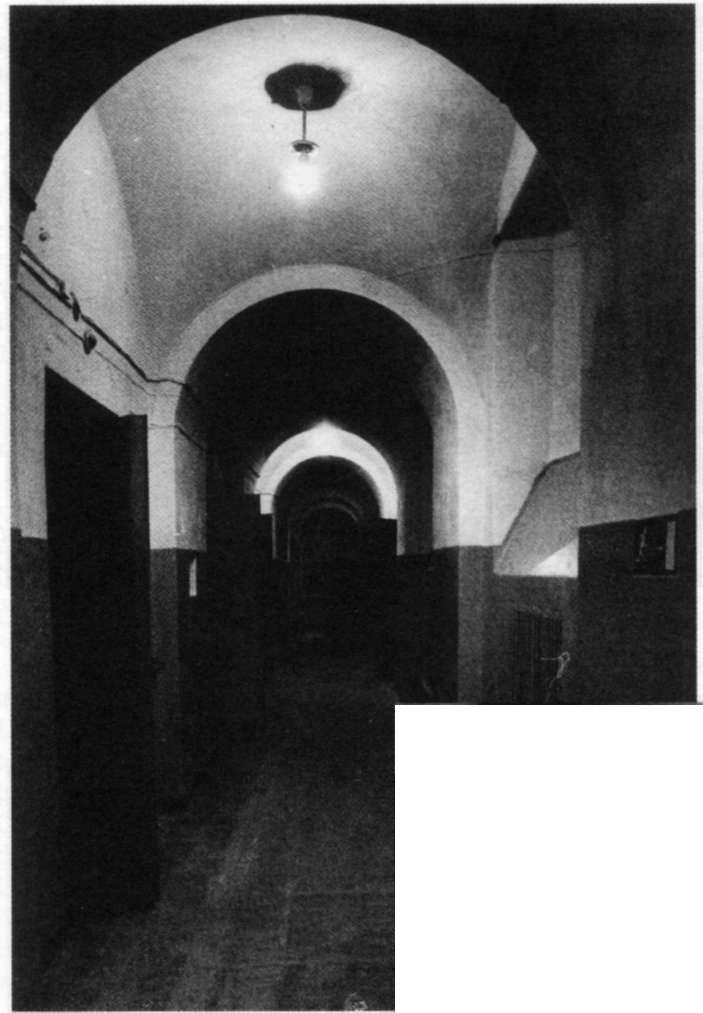

The NKGB (MGB, KGB) prison in Vilnius in which all the arrested bishops and contributors of the Kronika were imprisoned.

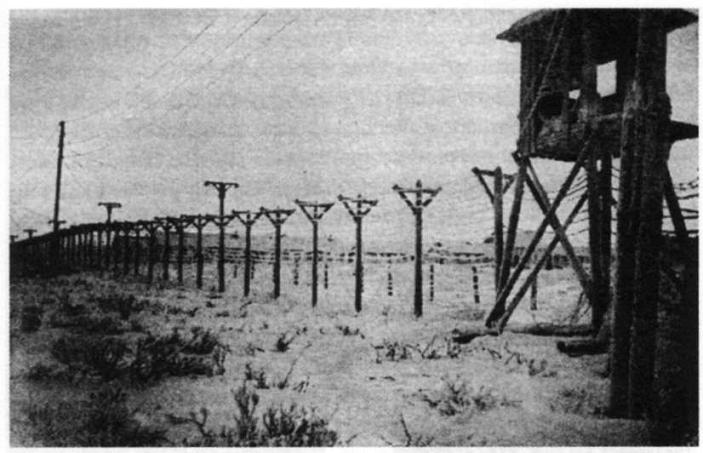

Living zone of the Vorkuta gulag

Funeral of a Lithuanian exile in the Irkutsk region. 1953.

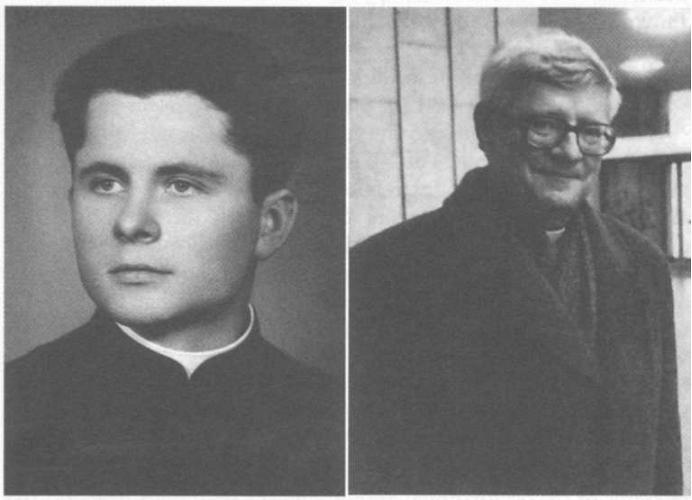

Lithuanian Catholic Bishops repressed in 1946-1947

Archbishop Mecislovas Reinys Bishop Vincentas Borisevičius

(Photo from KGB archive) (Photo from KGB archive)

Bishop Teofilis Matulionis Bishop Pranciškus Ramanauskas

(Photo from the camp) (Photo from the camp)

(The dynamics of churches, priests and theological students is illustrated in Table 2)

Table 2

Lithuanian Catholic Churches, Priests* and Theological Students in 1940-1988

Year Churches Priests Students Notes

1940 732 1579 Appr. 450 Appr. 1500 monks and nuns

1945 711 1232 318

1948 711 1012

1951 670 750 63 129 parishes had no priest

1953 672 734 72

1955 663 772 The priests began returning from gulags

1957 663 929 76

1960 662 922 56 Number of students reduced to 60 in 1959

1963 638 884 31 Number of students reduced to 30 in 1961

1966 630 877 24

1970 630 815 Number of students increased to 50 in 1969

1975 630 756 61 parishes had no priest

1980 630 704 81 105 parishes had no priest

1986 630 664 131 This year number of priests was smallest

1988 632 678 142 160 parishes had no priest

* Only the officially appointed priests are included; the priests who graduated from the underground seminary and those deprived of the certificate of priest registration were not included in the documents of the representative of the RKRT. The table is made according to the documents from LCVA, F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 22, 27, 29, 36, 47, 58, 66, 70, 79, 99, 105, 123, 136 and C. d. 1, f. 86, 124.

After the thaw policies (1953-1956) of Nikita Khrushchev ended, the fight against 'nationalism' as well as religion became more severe. In 1957-1958 a new wave of arresting priests arose: 13 priests were arrested on charges of anti-Soviet propaganda, incitement of nationalism, or keeping anti-Soviet literature. For the most part they were the creative and active priests who had returned from the gulags.

The repressions against the priests in the 1980s were connected with the underground press and the fight for the rights and freedoms of believers.

In addition to the priests, hundreds of monks and nuns as well as laymen were repressed during the Soviet era for protecting the rights of the believers, participating in religious activities, publishing religious literature, and fostering the religious upbringing of children and youths. A particularly large number of schoolchildren and students was sentenced for this in the post-war years.

Soviet repressive institutions used methods of unlawful violence against people who were not acceptable to them. Using such measures Rev. Juozas Zdebskis was chemically burned and barely escaped death on 3 October 1980.26 However, on 5 February 1986 he died in a car accident which, many believe, was organized by the KGB. It is believed that on 2-3 February 1947 the MGB fatally poisoned administrator (vicar capitular) of the Kaunas Archdiocese prelate Stanislovas Jokubauskis. Apparently, he was an obstacle in carrying out the MGB strategic plan to concentrate the management of the whole Catholic Church in Lithuania in the hands of one acceptable person - agent 'Neris'.27 (This plan did not succeed: the Vatican hindered it by not consecrating him as a bishop and Bishop Matulionis returned after being released from prison). It is likely that in December 1948 the MGB liquidated (by shooting him in Laisves alėja in Kaunas) its own agent 'Kardas' - the Franciscan priest Stasys Martušis28 - who had become dangerous for them and who, among other tasks, was to help separate Lithuania's Catholic Church from the Pope. It can be suspected from the summaries of recordings by the KGB and the acts of KGB officers that on 20 August 1962 they fatally poisoned Bishop Matulionis. It is believed that they murdered the priests Leonas Šapoka (in 1980) and Leonas Mažeika (in 1981) for trying to escape from the KGB web. Some people claim that the well-known fighter for the rights of the believers Rev. Bronius Laurinavičius was pushed under a truck and killed in Vilnius in 1981.

Demoralization. The demoralization of priests was used as often as repressions. The KGB did not have special goals in demoralizing priests; its aim was to make them subordinate or to recruit them. However, recruitment and break down led the priests not to listen to their conscience, disregard it and finally to the decay of the priestly spirit, which in turn led to hard drinking, debauchery, breaking of celibacy, etc.

As mentioned above, the KGB directed their main attention to the hierarchs and other priests in responsible position. No priest, however, totally escaped the attention of the KGB. The number of priests recruited as agents varied in different periods. This depended not only on the resistance of the priests against recruitment, but also on the needs of the KGB. For example, 77 priests were working in Kaunas in August 1945 and in August 1946 there were 6 priests-agents.29 There were 60 priests and bishops working in the city and district of Kaunas in 1985. Among them at the end of 1989 (before the regaining of independence) there were 18 priests-agents.30

--------------

26 Lietuvos ypatingasis archyvas (LYA) [The special archive of Lithuania) -formerly the Archive of the KGB of the LSSR . F.K-1, C. d. 45, f. 504, sh. 102.

27 ibid. C. d. 14, f. 59, sh. 17-19 (as well as torn off sheets 15, 16).

28 ibid. F. 73, sh. 140-152; f. 81, sh. 163, 164.

29 ibid. F. 32, sh. 50; F. 56, sh. 14-31.

30 ibid. F. 205, sh. 19-21.

The position of the KGB was much worse in the provinces. Even in the 1980s, the KGB stated that they did not have a single priest-agent in some districts. In 1956 out of 899 priests working at that time there were only 60 priests-agents, or 6.7 percent.31 It is likely that this percentage increased during the following decades, but taking into account that there was a KGB officer in every district caring for the clergy and that the KGB tried to recruit every priest (many of them several times) it can be stated that the priests of Lithuania passed this test quite well.

The Attempts of the NKGB (MGB, KGB) to Use the Church. While the Church was alive, while it had some influence on the population, the Soviet authorities wanted to use it to help achieve their political goals. As mentioned earlier, one of the main tasks of the Soviet authorities in Lithuania was to destroy the armed resistance - the partisans. In order to achieve this goal the authorities had also intended to use the institution having the strongest influence in society, the Catholic Church.

Already at the end of 1944 the NKGB began to take measures to force the hierarchs to condemn the partisan fight.

On 15 February 1945, Commissar of the NKVD of the LSSR Juozas Bartašiūnas issued a proclamation to the partisans in which he promised freedom and amnesty to those who surrendered. The authorities also wanted the clergy to support this proclamation, and thus in 1945 the pressure on the hierarchs intensified. The bishops were invited to visit the NKGB and were forced to write appeals to the partisans.

On 5 February 1946 all the diocesan administrators were invited to meet Deputy Chairman of the LKT of the LSSR Motiejus Šumauskas. The bishops were scolded for supporting the partisan fight and it was demanded that they write a group appeal urging the end of partisan fight. Two weeks later the bishops presented such an appeal, but the authorities rejected it as being anti-Soviet. In the subsequent year and a half all the bishops (except Paltarokas) were arrested.

Nevertheless, the partisan fight continued and the Soviet authorities continued to make attempts to make the Church obey their wishes. The resolution of the Bureau of LKP(b) CK, dated 12 December 1947, states: "...to use loyal priests in every possible way so that they would speak against bandit activities and the priests who support the bandits."32

The authorities were able to get a clearer separation of the hierarchs from the partisan fight only after the arrests of the bishops and the appointment in 1947 of canon Juozapas Stankevičius as the administrator of the Kaunas Archdiocese. From that time the careful, but desired by the authorities, "orientation of the clergy into positions loyal to the authorities" began.

-----------

31 ibid. C. d. 3, f. 532, sh. 91.

32 LYA. The archive of the documents of the Lithuanian Communist Party (further-LYA LKP DS). F. 1771, C. d. 190, f. 5, sh. 179-187.

The MGB, the representative of the RKRT, and the institutions of the local authorities would force the priests to support the various political and economic campaigns of the authorities: 'free' elections, supplying contributions to the state, the establishment of kolkhozes, etc. The local authorities abused their position of power to a great degree, and quite a few priests who did not please them were sent to prisons and exile.

In the beginning of the 1950s the Soviet Union began on an international scale the 'fight for peace' and the 'fight against the instigators of war' (but, in fact, for weakening the positions of the West in the world and strengthening the positions of communism). It was decided to use the support of the Church to gain international favor. At first, canon Stankevičius and later Bishop Paltarokas as well as some other priests participated in these conferences. (Bishop Paltarokas was never considered loyal, but as the only remaining bishop, he was used for his authority. The Bishop understood this and, in turn, used his position for the good of the Church. In 1953 he started demanding that his successors be appointed: he demanded that the bishops imprisoned in the gulags be released, and when this failed he obtained the permission of the Vatican to consecrate two new bishops - Julijonas Steponavičius and Petras Maželis, who were consecrated in 1955).

In later decades when the authorities had 'loyal' priests as the administrators of all the dioceses, they opened for Lithuania's Catholic Church the door to the world and to the Vatican wider. However, this opening benefited the authorities more than the Church. The main task of the priests who went to the so called Berlin conferences was "to demonstrate the freedom of the Church in Lithuania" and to neutralize the hostility to the Soviet Union. The hierarchs who went to the Vatican and their companions (and the priests sent to study there) not only had to collect the information the authorities wanted, but also if they had a chance to influence Vatican policy in a direction useful for the Soviets. This task became even more important after John Paul II became Pope in 1978 and the KGB of the USSR included the KGB of the LSSR in its planned operations. On 17 March 1980 the Lithuanian KGB began the special agent observation case 'Capella.'33 While fulfilling the tasks assigned by the PGU* of the USSR KGB in this case, the main stress was put on the priests - KGB agents - who were going to the Vatican (or to other Catholic Church organized events). Their task was to diminish anti-Soviet tendencies, to influence the Vatican to support or at least not oppose the political initiatives of the USSR. After the independence movement began in Lithuania in 1988, their task was to influence the Vatican not to support radical forces and to restrain the priests from

----------

33 LYA. F.K-1, C. d. 49, f. 232, 233.

* PGU (Pervoe glavnoe upravlenie) - the First Main Department, which dealt with foreign spying.

joining this movement so that "it would not harm the democratization policies carried out by Mikhail Gorbachev". The assignments, however, were not limited to only Lithuania. Through the Vatican they even tried to influence U.S. President Ronald Reagan, the fate of the war in Afghanistan, etc.

During the whole Soviet occupation the goals of the authorities concerning the Church did not change: to exterminate it, to eliminate it from life, and to make use of it whenever possible. It was granted as much freedom as was useful for the foreign and internal policies of the USSR. Thus, the clergy faithful to Catholic Church had no other choice but to resist the limitation of the rights and freedoms of members.

2. THE RESISTANCE OF THE CHURCH

In the beginning of the occupation (in 1940) the hierarchs, as was proper, were the first to begin the fight against the restrictions of Church activity.

When the Soviets occupation returned to Lithuania in 1944 the bishops of Lithuania (on the initiative of Bishop Matulionis) gathered in a secret meeting in Ukmergė on 5 September in order to discuss the most urgent problems of the Church, such as religious education, the establishment of the positions of chaplains in the small Lithuanian units of the Soviet army, the operations of the theological seminaries, etc. Learning about this meeting, the KGB broke it off the following day.

The bishops of the Catholic Church in Lithuania understood well the importance of unanimity in resisting the restrictions and the demands of the authorities which were incompatible with Church law and practice.

Seeking to weaken the resistance of the hierarchs, the authorities began the method frequently used by the NKGB - splitting and opposing -but this method was not very successful. Until 1947 they did not have a single diocesan administrator 'loyal' to them ('the loyal' were usually recruited by Soviet security). There was no alternative other than to arrest all the bishops except one, Kazimieras Paltarokas, who seemed to appear more compliant (but he was not 'loyal' and he was never considered as such - author) and to appoint capitular vicars (administrators) in place of the bishops. This was completed by the middle of 1947. However, the new administrators did not turn out to be better, thus in 1949 half of them were arrested and one was exiled from his diocese. With the direct intervention of the representative of the RKRT not fully 'loyal' but at least more loyal administrators were put in their positions.

In 1956 Bishops Matulionis and Ramanauskas returned from the gulags. Seeing the spinelessness of some of the diocesan administrators,

they tried to support Bishop Paltarokas and to unite all the administrators around him so that it would be easier to resist the pressure of the authorities. The authorities, however, resisted these attempts with the help of 'the loyal' administrators and planned to arrest them again or to exile them from Lithuania. (However, they settled for only exiling them to distant parishes in Lithuania and isolation from other administrators).

After the end of the war any meeting of the administrators, diocesan capitulas, or the deans was forbidden without the permission of the representative of the RKRT. The solidarity of the diocesan administrators improved somewhat when the colleges of administrators started functioning after the Second Vatican Council. Although the trips of the hierarchs to the Vatican were controlled very strictly and the authorities tried to get from them as much benefit as possible for the policy of the USSR, the judicial dependence of the Catholic Church on the Pope provided a powerful weapon of motivation to the hierarchs of the Church in Lithuania to resist the anti-canonical demands of the authorities and make more difficult the interference of the authorities into the internal life of the Church.

The resistance against the restrictions of Church activity and the initiatives to fight for the rights and freedoms of the believers usually came from the priests who were appointed to small parishes and to whom "it was more important to listen to God than to people" (St. Peter's words). In the documents of the KGB and the representative of the RKRT they are mentioned as 'religious fanatics', 'extremists,' or 'reactionaries'. Their leaders in the 1960-80s were Bishops Julijonas Steponavičius and (promoted to cardinal in 1988) Vincentas Sladkevičius both of whom were in exile. When the movement of national liberation had progressed, Cardinal Sladkevičius declared at a symposium of priests in Kaunas on 3 August 1988 an actual ultimatum to the Soviet authorities: the Church refuses to obey limitations and it will act independently in the future.1 This was one and a half years before the re-establishment of independence.

The Phases, Methods, and Measures of Resistance. There was opposition to the restrictions of Church activity during the whole period of occupation. As mentioned earlier, the hierarchs led this resistance in the first post-war years. After losing the Church's most persistent leaders and priests through the repressions, the Church in the 1950s did not try so much to resist but to maintain the positions it had. The priests and bishops who survived and returned from prisons and exile in the middle of the decade brought back some revival and courage as did the liberation hopes which became stronger after the death of Stalin not only in the Baltic states but also in the Communist controlled countries of Central Europe. Clearer instances of resistance appeared in the 1960s. A new

--------

1 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 135, sh. 5.

generation of priests educated in the post-war years matured. They did not have any personal experience with repressions and thus were more courageous. They quickly found a common language with the courageous priests with unbroken spirit who had returned from the gulags. Around 1966 the more diligent priests began to hold secret meetings which discussed the situation of the Church and guidelines for activity. It was obvious that the door to the Vatican was opened slightly for the hierarchs and the Vatican approval of their rule served more the interests of the authorities than the Church. During one of these meetings the idea to write collective declarations of priests to the hierarchs and the authorities demanding freedom of action for the Church and defending the rights of the believers was born. From 1968 hundreds of such declarations (later laymen also joined this action) were sent not only to the hierarchs of the Church and the authorities but also to international organizations. The idea to publish an underground journal, which became the voice not only of the fighting Church but also of the whole nation, was proposed in one of these meetings. It became the Lietuvos Kataliku Baznyčios Kronika (hence Kronika). At the end of the 1960s the occupation authorities noted that the activity of the Catholic Church in Lithuania increased.

The public Catholic Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Believers (hence - TTGKK), established on 13 November 1978, proclaimed its aims to be to observe that the laws of the USSR concerning matters of the Church and the believers would not contradict the international agreements signed by the USSR, to explain these rights to the believers, and to protect them. The publishing of the Kronika and its distribution throughout the world as well as the activity of the TTGKK marked a new phase of Church resistance against the Soviet regime and gave a new impulse to the liberation movement of the Church and the whole nation.

We will briefly discuss a few areas of Church activity, whose restrictions were particularly resisted, and the forms of this resistance.

Religious Education of Youth. After the teaching of religion was removed from the schools in 1940, it was taught in churches. The teaching was organized in the following way: the teaching took place after the end of the school day in churches according to an approved schedule and according to classes. When the Soviets occupied Lithuania again in 1944, the hierarchs learned that it would be impossible to regulate this question with the authorities using civilized measures (submitting memoranda), and returned to this practice independently.

Two years later, in November 1946 the Council of Ministers of the LSSR extended the prohibition of teaching religion to children and youth to churches.

The catechization of children - their preparation for Confession and First Communion - was conducted in the same way as it had been done before the occupation: after the end of the school year priests taught the children in churches for 3-4 weeks. In 1947 the republic authorities decided that this teaching should also be forbidden. The official reports of the authorities state that collective teaching of children and youth in churches ended in 1950,2 but many priests consciously ignored this and continued to teach children religion during all the occupation. Other priests sought alternate forms of teaching.

All the priests understood the importance of catechization for the survival of the Church very well and, thus, despite the constant observation, bans, and penalties of the authorities, catechization did not stop during all the occupation: the representative of the RKRT and the so-called Control commissions for observing the law of cults, which functioned in every town and district, wrote many reports about the collective teaching of children. The reports of the representative of RKRT give information about the increase in the number of children who received First Communion. For example, 21,380 children received First Communion in 1975, and 25,034 children in 1978 while the corresponding numbers for the sacrament of Confirmation were 18,690 and 24,438, respectively.3

In 1981 the representative of the RKRT in Lithuania in his report to Moscow, the LKP CK, and the Council of Ministers wrote that almost all the priests were demanding permission to catechize children. Nuns actively helped in this task. He stated that "the Catholic Church considers itself as the only defender of the national and moral traditions of youth".4

Organizations. Several organizations were primarily concerned with the religious education of youth before the occupation. After the occupation all of them were closed, and their leaders were watched and repressed. For the first 3-4 years of the second occupation (from 1944) the Ateitininkai organization was quite active as an underground organization in many secondary schools, Kaunas University, the theological seminary, the teacher seminaries, and other schools of higher education.

In 1949 the MGB succeeded in revealing the underground religious-patriotic organization 'Aušros Vartų kolegija' (College of the Gates of Dawn) which was active in Vilnius. Most of its members were students of the Vilnius Pedagogical Institute and Vilnius University. The aim of this organization was to educate students in the spirit of the Ateitininkai to be willing to serve God and the Homeland so that after graduating from the universities they would convey this spirit to the youth in the schools.

----------

2 ibid. F. 35, sh. 18-29.

3 ibid. F. 103, sh. 33-36.

4 ibid. F. 108, sh. 276-282.

During the whole period of occupation the Pioneer and Komsomol organizations were the main tools to make the youth soviet and atheistic. In the post-war (and later) years young people were forced to join these organizations. The hierarchs and many priests spoke more openly or more cautiously against this pressure and the forced atheistic instruction of believing children. On 7 April 1945 Bishop Matulionis wrote an appeal to the Commissar of Public Education of the LSSR protesting against forcing the children of believers to join the atheistic Pioneer and Komsomol organizations.5

A religious-patriotic movement of youth became more active at the end of the 1960s. Its start was prompted by the worship of the Holy Sacrament supported by Jesuit Pranciškus Masilionis who in 1947 established the underground Congregation of the Sisters of the Eucharistic Jesus. A Sister of this congregation Gema Jadvyga Stanelytė with the help of diligent priests and other sisters began to unite the more diligent young people into the Friends of the Eucharistmovement. This was similar to a renewal of the activity of the Ateitininkai, but in underground conditions.

The movement of the religious-patriotic intelligentsia played a role in religious education. These secret gatherings of students and the intelligentsia held conferences, debates, and meetings with former political prisoners and at times even organized retreats.

Mass Media. Religious education is impossible without the transfer of information. There could not be any talk of using radio and television to fulfill this need because they were controlled by the state and would be used only for anti-religious propaganda. Religious press had been forbidden already in 1940 and the other press was very strictly censored and monitored by the KGB. Thus, only a few years after the end of the war there arose a shortage of literature needed for the religious education of children, and also catechisms. The former pupil of the Salesian Fathers Paulius Petronis tried in 1963 to organize their underground publishing, but failed. However, from 1969 he began quite intense publication. Seeing that the underground began to supply the believers with catechisms and prayer-books, the Soviet authorities at the end of the 1950s and in the 1960s permitted Canon Juozas Stankevičius to publish a few editions of the prayer-book he had prepared. The permission of the Chairman of RKRT (from Moscow) and of the Council of Ministers of the LSSR had to be obtained for every publication of religious literature whose press runs and scope were also severely limited and the publication censored.

During the whole period of occupation the legally published religious literature was limited to prayer-books, books necessary for liturgy,

---------------

5 ibid. F. 4, sh. 20, 21.

the New Testament, the documents of the Second Vatican Council, several editions of catechisms, the almanacs-reference books, and a few leaflets. One should mention that the possibility of publishing a journal for Catholics was discussed on two occasions - in the 1950s and in the 1970s, but the hierarchs understood that the authorities would use this journal to spread Soviet propaganda and lies about the 'freedom of the Church' and refused to publish it.6

The authorities had two reasons for allowing the publication (or publishing themselves) religious books: to weaken the influence of the Vatican and the so called 'emigration centers' on the Catholic Church in Lithuania and to refute 'the slanders spread about the limitations and persecutions of the Church and the believers'7 by the 'reactionary' priests of Lithuania using the Kronika, the TTGKK, and other methods.

Philosophical and theological literature needed for religious education, the strengthening the spiritual life of the clergy (priests and underground monks), and sermons was only published underground. Paulius Petronis, Petras Plumpa, Jonas Stasaitis and others were among the most active publishers of underground religious literature. Thousands of Lithuanian Catholics participated in this work. They became the organizational and material basis for publishing the Kronika.

Resisting the Destruction of the Church. As mentioned earlier, repressive measures were used very often against the Church during the rule of Stalin (until 1953). Plans for the rapid destruction of the Church were dominant in the anti-church policy of that time. From the beginning of the rule of Nikita Khrushchev (1953), the plan for the rapid destruction of the Church was gradually abandoned and replaced by a long-term plan for its weakening and gradual elimination from life. As relations with the Western world grew, the anti-church policy of the USSR was forced to put more efforts into defending itself from the hostile opinion of the world and to seek even more secret and refined ways of fighting against the Church. The ways and measures of Church resistance also changed.

The Fight for Loyalty to the Universal (Catholic) Church. Moscow (Chairman of the RKRT Igor Polianskii) already on 8 May 1945 demanded the separation of Lithuania's Catholic Church from the Pope. He suggested the establishment of a so-called autocephalous Church and its union with the Orthodox Church. But even the LKP(b) CK opposed this. The problem was that the Catholics and the Orthodox believers in Lithuania (unlike in Western Ukraine or Belarus) were of different nationalities: the former were Lithuanians while the latter were Russians. Moreover, Catholics comprised 80 percent of the population, and there

----------------

6 ibid. F. 44, sh. 12, 16; F. 97, sh. 4.

7 ibid. F. 105, sh. 2-9.

were only 23,000 Orthodox believers. Furthermore, such a step would be regarded as the Russification of Lithuanians and the priests would have strongly opposed it. The LKP(b) CK suggested splitting the Catholic clergy and using 'loyal' priests to organize a national church.8 In 1946-1947 the chairman of the RKRT more than once told his representative in Lithuania that his primary task was to separate Lithuania's Catholic Church from the Pope.9

The representative of the RKRT and the MGB were involved in this issue, while the LKP(b) CK approved strategic issues. In 1946-1949 using the 'loyal' priests (MGB agents 'Šimkus', 'Kardas', 'Jurij', 'Tupėnas' and others) they more than once tried to organize the separation. However, the attempts kept failing. They clearly did not manage to gather even a minimal group of priests who would dare to talk about this publicly.

After Pope Pius XII issued a decree against Communism on 13 July 1949, the representative of the RKRT Bronius Pušinis prepared the statement "We strictly condemn and voice our protest" and sent it to the chairmen of the executive committees of the districts to collect the signatures of all the priests on it.10 On the basis of this protest signed by all the priests the separation of Lithuania's Catholic Church from the Pope would have been announced. However, this attempt also failed. The representative of the RKRT complained that the 'progressive priests' (those who signed it) were attacked by the diocesan authorities. He stated "we admit that we lost in this work."11

The KGB always suspected that there were some secret relations with the Holy See and tried to track them down. In 1947 such a channel was established by Rev. Pranas Račiūnas MIC through the French priest Labergue, who worked in the St. Louis Church in Moscow, but the security soon discovered this connection and arrested Račiūnas. They, however, did not succeed in tracking down the suspected channels of connections used by Bishops Paltarokas and Matulionis. In later years they suspected that the relations were kept through the clergy of Poland.

After the death of Stalin, the policy grew milder; they abandoned the idea of establishing a national church and decided to allow the leaders of the Catholic Church in Lithuania to establish very limited relations with the Vatican. The first such action was allowed in 1955 in presenting the candidates for new bishops.

The authorities always interpreted the relations of Lithuania's Catholic Church with the Vatican as an inevitable evil because the Vatican and the so-called Lithuanian 'emigration centers' (especially local priests)

----------------

8 ibid. F. 4, sh. 23, 24.

9 ibid. F. 10, sh. 4-7.

10 ibid. F. 19, sh. 4, 6.

11 ibid. F. 19, sh. 13-15; F. 21, sh. 40-144.

were considered to be the inspirers and organizers of the fight for the rights of believers in Lithuania. Although this was an exaggerated evaluation (perhaps intended to reduce the value of the resistance inside the country), it was also partly true. According to KGB data there were more than 630 Lithuanian priests in the West (in 1984),12 while only about 680 priests were left in Lithuania. Msgr. (now Cardinal) Audrys Juozas Bačkis was a secretary assistant of Public affairs in the Vatican in the 1980s. It is understandable that in spite of all the counter-measures taken by the Soviet authorities their influence on the Catholic Church in Lithuania was strong.

The strictly controlled by the authorities relations of Lithuania's Catholic Church with the Vatican and the Church of the free World began to expand in the 1960s. However, the authorities also pursued their aims all the time. Among the aims worth mentioning were: 1) to obtain the Vatican's approval that the policies of Lithuania's Catholic Church correspond to the wishes of the authorities and that the priests nominated for bishops would be acceptable to the authorities; 2) to gather information about the policy of the Vatican and influential Lithuanian priests abroad; 3) to influence the Vatican and Catholic Church in the West so that they would not support the 'reactionary' priests of Lithuania's Catholic Church and their fight for the rights of believers; 4) to spread the propaganda that the priests and the believers of Lithuania enjoyed all freedoms; 5) to influence the leaders of the Vatican so that not only the Vatican but also other countries of the Western world would pursue a foreign policy favorable for the USSR. For these aims the first priests of Lithuania were allowed to study in the Vatican in the end of the 1950s, and the priests selected by the authorities were allowed to participate in the sessions of the II Vatican Council in the 1960s (the hierarchs, invited by the Vatican but not acceptable to the authorities, were not allowed to go).

The hierarchs (or other priests) in addition to their direct aims of discussing issues concerning the internal life of the Church (it was usually coordinated with the authorities after long and boring discussions) had to perform some other of the just mentioned tasks. Thus, during the Soviet period the evaluation of the relations of the hierarchs of Lithuania's Catholic Church with the Vatican can not have one evaluation and it will remain controversial. However, generally evaluating the value of these relations, they have to be admitted as positive: the preserved loyalty of Lithuania's Catholic Church to the Holy See left in the hands of the hierarchs a powerful weapon of juridical motivation to resist the pressure of the authorities on the grounds of necessity to follow the law of the Church. A word should be said on behalf of the hierarchs terror-

-----------

12 LYA. F.K-1, C. d. 49, f. 499, sh. 10.

ized by the authorities: even the weakest, even those hierarchs who were caught in the snare of the occupants did not destroy the Church maliciously. The deepest respect goes to the leaders of the fighting Church (the exiled Bishops Steponavičius, Sladkevičius, the editors of the Kronika, the Catholic Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Believers) who, although sometimes openly reminding the hierarchs about their responsibilities and urging them to execute them, while receiving undeserved punishments and reproaches in return, did not condemn and judge the hierarchs in public. This in part can explain why there was no division between the fighting and subservient parts of Lithuania's Catholic Church and why today there is no great conflict between the representatives of these parts which is quite visible in some other former Communist countries.

The Fight for Preserving Churches, Monasteries, and Priests. One of the measures the Soviet authorities used to try to take the management of the Church into their hands was the registration of religious societies, cult buildings, and priests.

From the very beginning the hierarchs of the Catholic Church in Lithuania severely resisted these demands of the authorities. Archbishop Reinys, Bishops Matulionis and Paltarokas were considered to be the leaders of the resistance among the hierarchs. Capitular vicars prelate Bernardas Sužiedelis and canon Vincentas Vizgirda supported them. One of the reasons for the fierce resistance of the hierarchs, according to the representative of the RKRT, was the unwillingness of the hierarchs to lose control in appointing priests (because the approval of the representative of the RKRT would also be needed after registration).13

The registration of churches began only in the middle of 1948 after the arrest of almost all the leaders of the hierarch resistance: Archbishop Reinys and Bishops Borisevičius, Matulionis, Ramanauskas. The authorities undertook the most brutal measures: the officials of the Vilnius archdiocese and the Telšiai diocese were thrown out of their premises in 24 hours, churches were sealed, priests were thrown into the streets, declaring that they were not registered and were working illegally while parishioners were also threatened and blackmailed.14 In the atmosphere of such political and economic terror, threats, and repressions the authorities succeeded in breaking down the resistance and the registration of churches was begun. On 1 January 1949, 677 out of the 711 churches which functioned earlier were registered and 34 were closed.15

The new representative of the RKRT Bronius Pušinis declared joyfully to Moscow that the priests already knew that "the diocesan office only presents their candidacies for assignment (to parishes) while the

-----------

13 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 9, sh. 53-59.

14 ibid. F. 13, sh. 53.

15 ibid. F. 17, sh. 5.

Representative appoints them" (Moscow scolded him for talking publicly about this).16

During the whole period of the Soviet occupation the authorities tried to strengthen the influence of the church committees on the work of priests in order to limit their spiritual work and leadership in the parish. The authorities, however, did not succeed in making the church committees tools of anti-church policy. As a rule, the committees either supported the pastor or did not interfere with his activity.

The registration of churches and priests was not only a measure which helped the authorities to meddle in and influence the internal life of the Church, but also provided an excellent opportunity to close churches, and not to allow unacceptable priests to work officially as priests.

The first places of worship to be closed were the churches and chapels of monasteries and cloisters, especially those which had no permanently residing priest. In May 1945 the chairman of the RKRT demanded information about the most influential monasteries: the Jesuits, Marian Fathers, Salesians, Franciscans and cloisters: the Sisters of St. Benedict, of St. Casimir, of St. Catherine, of St. Elizabeth, and the Sacred Heart of Jesus.17 The start of the registration of religious societies in 1948 gave the authorities a good chance to destroy the monasteries and cloisters. They were simply not registered, the monks and nuns were evicted from their premises and their churches closed. All monks who were priests were also not registered, the representative of the RKRT considered them as unemployed and an indication that there was an excess number of priests in Lithuania. He regarded the loss (the nationalization) of the land and the buildings of the monasteries and the transfer of monk priests to work in parishes as the reasons for the 'self-liquidation' of the monasteries.18

It was impossible to resist the liquidation of the monasteries (the deprivation of land, buildings, churches, and all property). The claims of the representative of RKRT about the 'self-liquidation' of the monasteries were, however, total lies because the monasteries did not liquidate themselves, but went underground. During the years of the occupation the Jesuits, Marian Fathers, Franciscans, and many orders of nuns not only did not simply disappear, but fostered many holy personalities and developed a deep vein of evangelization not only in Lithuania but also in vast expanses of the Soviet Union. According to KGB data in the 1980s there were 1,300-1,400 monks and nuns in Lithuania. In Kaunas alone (in 1985) there were 350 nuns and 160 youths in their promoted Friends of the Eucharist. In that year one KGB officer fol-

----------------

16 ibid. F. 14, sh. 35-38, 98-100.

17 ibid. F. 4, sh. 19.

18 ibid. F. 19, sh. 20-24.

lowed the activities of the 60 priests and the 117 seminarians in Kaunas, but three KGB officers watched the nuns and Friends of the Eucharist.19

Priests and the Theological Seminary. As was mentioned earlier, the authorities had two aims concerning the priests: to reduce their number (by repressing them, not allowing them to work, and not allowing new ones to be prepared) and to eliminate them from active life (to limit their activities, to demoralize and isolate them from society).

During the campaigns for closing churches (especially in 1948-1949) the representative of the RKRT at one time proposed to leave only one priest in every church and on another occasion to allow only one church in a district. However, these outlandish proposals receive no support in Moscow (they were afraid of the discontent of the population).

In the post-war years the number of priests was reduced mostly using repressions: arrests and exiles. The hierarchs could not oppose this.

In 1951 representative of the RKRT Pušinis in a letter to Chairman of the RKRT Polianskii wrote that the number of priests was mostly reduced by arresting them. This, however, did not reduce the piety of the people - and it could happen as it did in Western Belarus where the believers regard the rarely met priest as a savior - and he is saying that he is going to appeal to Antanas Sniečkus to stop the arrests.20

Another way to reduce the number of priests was by lowering the number of students admitted to the only seminary in Kaunas. In the 1945/1946 school year there were 318 theological students. In 1946 the limit was reduced to 150 and in 1949 down to 75 because of the 'excess and unemployment' of priests. In 1959 the number of students was reduced to 60, and from the 1961/1962 school year not more than 5 youths could be admitted to the first course. In 1965 the seminary reached its minimum: only 24 students.21

As mentioned earlier, the secret meetings of diligent priests began in 1966. One of the most urgent subjects discussed at the meetings was the physical extermination of the Church carried out by the authorities. After collecting the signatures of priests from the Vilkaviškis diocese, Tamkevičius, Zdebskis, and other priests appealed several times in 1968-1969 to the administrators of all the dioceses and the Soviet authorities concerning the fate of the theological seminary. In 1969 the limit on the number of students was slightly increased - up to 50 - and the limit on the number of admissions to the first course up to 10 students.22 It was clear that the increase was pure political cosmetics and could not solve the problem when 20-30 priests died every year.

-----------

19 LYA. F.K-1, C. d. 14, f. 205, sh. 19-36.

20 LCVA. F.R-181, C. d. 3, f. 27, sh. 5.

21 ibid. F. 70, sh. 30.

22 ibid. F. 79, sh. 152.

In 1971 Rev. Zdebskis organized an underground theological seminary where those not admitted by the authorities to the official seminary could study. After a while the strongest religious orders in Lithuania, the Jesuits and Marian Fathers, took over control of the underground theological seminary. Not only Lithuanians but also Ukrainians, Byelorussians and candidates from other republics studied there. Although the authorities did not allow the graduates to serve officially as priests, nevertheless they found ways to be apostles not only in Lithuania but also in other regions of the Soviet Union.

In 1977 the authorities raised the annual limit of new admissions to 20 and doubled (up to 100) the overall limit for the seminary. In 1981 this limit increased to 140 and in 1988 up to 150 students.23

Even though the limit was increased from 1969, the number of new priests could not compensate the number of deaths until 1987. In 1945 there were 1,232 priests in Lithuania, but because of repatriation (to Poland), repressions, and deaths only 734 were left in 1953.

Out of the 362 priests repressed only 249 priests in 1955-1957 returned to Lithuania alive and increased slightly the number of the priests in the country to 929 in 1957. However, in the following years their number decreased constantly and in 1986 only 664 priests were left. From 1987 this number began increasing very slightly. Thus, in comparison with 1945, during 40 years the Soviet authorities managed to reduce the number of the priests almost by half.

Another aspect of the annihilation of the Church was the physical destruction of places at which the faithful worshipped. Among such places in Lithuania were Šiluva, Žemaicių Kalvarija, Vilniaus Kalvarija, Veprių Kalvarija, Aušros Vartai (the Gates of Dawn) in Vilnius and the Hill of Crosses. The Soviet authorities considered such places as 'centers of religious fanaticism' and planned to destroy them.

In 1962 many of the chapels at the Veprių Kalvarija were destroyed.24 The same year, according to resolution No. 889 of the Council of Ministers of the LSSR, all the chapels of Žemaicių Kalvarija were closed and handed over to the local authorities, but the people opened them independently and conducted processions during the time of the usual Church festivals there.25 In 1962-1963 most of the chapels in the Vilniaus Kalvarija were destroyed. However, this did not discourage the believers and in 1969 the representative of the RKRT stated that the number of pilgrims increased in Šiluva, Žemaicių Kalvarija, and Vepriai.26

In 1971 the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union passed the resolution 'On the Intensification of Atheistic

------------

23 ibid. F. 108, sh. 259.

24 ibid. F. 84, sh. 68-72.

25 ibid. F. 64, sh. 47, 48.

Education of the Population' in which great attention was given to the struggle against the visiting of 'holy places'.27

However, neither this nor other secret resolutions of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party and the Council of Ministers on how to halt the visiting of places of worship helped, but on the contrary - the visiting intensified. Mass processions were organized to Šiluva and other places of worship.

The Fight against Restrictions on Priests. The Soviet authorities tried to weaken the influence of the clergy on society by using different measures, starting with bans and limitations and ending with repressions.

In order to isolate the priest from society, the authorities introduced many limitations on priestly work. For example, it was forbidden for children to participate actively in liturgical rituals, such as serving as altar boys during Masses, taking part or strewing flowers in processions, singing in church choirs. In 1949 processions were forbidden (except during funerals), including the traditional processions to cemeteries on All Saints Day and to the places of worship (Šiluva, Kalvarijos, etc.). The same year the meetings of priests and of the diocesan capitula were forbidden without the permission of the representative of the RKRT.28 In 1950 priests were forbidden (without the permission of the local executive committees) to conduct any liturgical rituals beyond the borders of their parishes.29

Already in 1947 priests were forbidden to administer the sacraments to the sick in hospitals without the permission of the head physician, and if allowed they had to be administered in a separate room and not in the ward.30 Thus, the priests usually gave the last rites secretly even though this was often very inconvenient for the dying patients. Nuns who worked as nurses and hospital attendants at the hospitals helped make this possible. However, more than one patient died without receiving the last rites because of this ban. The Kronika wrote about such cases quite often.

The first prohibitions of ringing church bells were issued around 1952-1953, but the official prohibition of ringing church bells was made in decision No. 28 of the Council of Ministers, dated 10 January 1967.31

In order to suppress even more the impressive influence of church services on believers, the activity of church choirs was restricted; it was forbidden to organize choir rehearsals outside church walls (in winter it was cold to rehearse in the churches) and the choirs were permitted to

----------------

26 ibid. F. 79, sh. 110.

27 ibid. F. 84, sh. 54.

28 ibid. F. 18, sh. 10.

29 ibid. F. 24, sh. 16.

30 ibid. F. 11, sh. 30.

31ibid. F. 136, sh. 12-16.

sing only in their own churches. In 1956 it was forbidden to install radios in the churches and churchyards.32

In secret instruction No. 4-69s the chairman of the RKRT obligated his representative in Lithuania, Justas Rugienis, to forbid priests to make traditional visits to parishioners, and the official document banning this practice in Lithuania was passed on 16 June 1962.33

In spite of the bans and threats, priests took risks to fulfill their priestly duties. They were especially watched and punished for the catechization of children and work with youth. In those days the most often imposed punishment was taking away the priest's certificate of registration. If they were deprived of the certificate, the priests had to find employment as ordinary workers. In 1962 six priests were deprived of their certificates, and in 1963 - 14 (that year only 13 new priests graduated from the theological seminary). A milder punishment was to transfer such a priest to some remote place.