(Miss) Ona Pranskūnaitė writes

November 2, 1977

My dear, today I visit that garden of the dead in my thoughts. This year, I will not have an opportunity to light a candle on a neglected grave; my heart will not rejoice at thousands of flickering candles; I will not hear any mournful organ prelude, I will not have the good fortune to send to the other shore the graces that flow from Holy Mass. But, in my view, that is not the most important thing. Most important is how one spends the allotted time. I want to find my happiness in doing what I can do ... .

December 24, 1977

Thank you for your Christmas gifts. They did not give them to me. They attached the card and wafer to my personal file. The star on the card baffles them: it does not have five points. They wondered among themselves whether something had not been baked into the wafer (.. .). If possible, could you please send me a package? Its contents should be: .5 kg. (1 lb.) smoked cheese, .5 kg. (1 lb.) butter, and the remaining weight in smoked bacon. The weight of the package not to exceed 5 kgs. (10 lbs). Please do not include sausage, head cheese or other products in the package, because they will not give them to me. The package will reach me in about a month.

... A note of longing for the Motherland echoes throughout my letters. Please don't misunderstand me. If God were to wish it and it were useful, I would agree never to see her with my mortal eyes. But the Motherland is very precious and dear to me. And if I were not to tell her of my longing love in words, it would mean I do not love her.

We work hard. Sometimes even 14-15 hours a day, but I feel no particular fatigue. I sleep poorly at night. Songs are heard in the colony zone at 2:00 A.M.: it is the second shift returning from work. I would not say that those songs ring from a glad heart, they most frequently ring from an inside void . . .

I thank you, children of Mary's Land, for your prayers, concern and longing for good! Day after day, I send to you my countrymen, through God's gracious hands, those gifts which abound in my life. God go with you!

January 8, 1978

I am forbidden to write in Lithuanian, or to receive letters written in Lithuanian. I am fighting this with the local government. They do not believe that Vilnius censors my letters. I will not renounce writing or speaking my native tongue so long as a single drop of warm blood remains in my veins. If in the future you do not receive any letters from me, know that they are forbidden. I would like to continue corresponding, for every contact with people, regardless of the method, brings people together just as a long silence makes them strangers. I've become very stubborn: this is an unfortunate character trait.

The clothing you sent was placed in the personal effects storeroom. After I complete my sentence, they will be returned. I was issued a prison-type uniform. We are not supposed to be cold in it, because our "solicitous" officials have so determined. I was given new high top shoes, size 13. Both feet fit into one shoe. If they did not have holes, I could swim across "mother" Volga but because of bad "seams" I sank in the colony yard last fall.

In one letter you wrote that God will perhaps lead me back to the Motherland. My dear, the time to return may come. But I wonder if the specter of death will not meet me on the way home ....

January 23, 1978

. . . We work very long hours. We only have one free Sunday per month. My health is a little better, but for how long? (...)

February 20, 1978

. . . Children of Mary's Land! May God's grace rain dew upon you. Do not be fearfully worried; be wise and strong . . . Always with you in prayer and suffering and dreams!

March 9, 1978

I wait for your letters. One finally arrived but... it is so heavy,

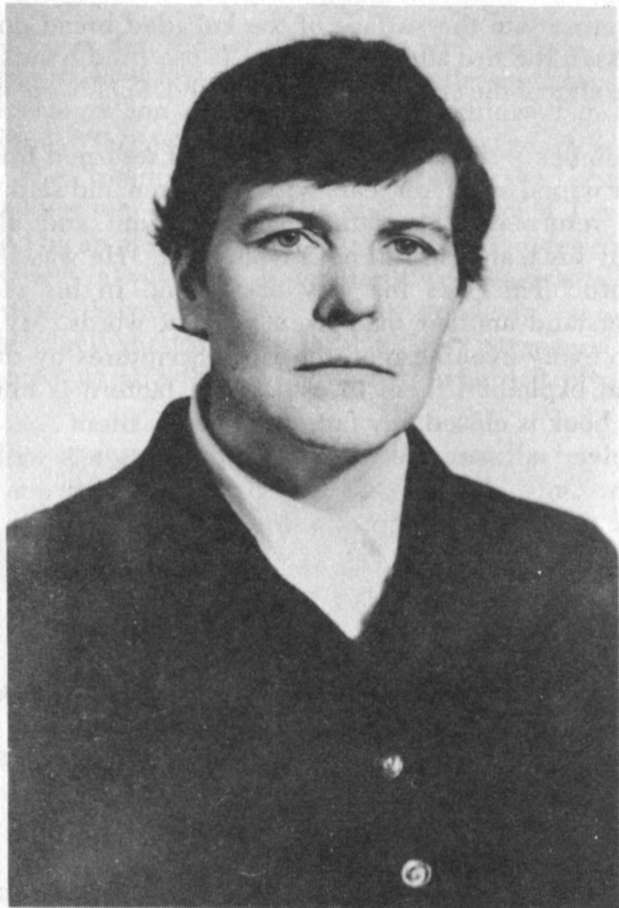

Ona Pranckūnaitė, referred to as a "nun" by her interrogators. The date of the photo is unknown.

as though made of lead. I wanted to destroy it. But the date: died the 18th, buried the 22nd . . . Buried . . . Someone buried my mother. . .

I did not receive the telegram . . .

Children of Mary's Land! Be devoted to God, be obedient to his every gesture.

March 20, 1978

. . . Before my eyes I see the hands of my mother forever folded in prayer: those hands which led my fragile little hand from brow to breast, teaching me to make the sign of the cross. Those hands which pressed a cross into the surface of the kneaded bread dough, hands which blessed the fire after lighting it. Those tired hands every time making the sign of the cross over the little bed. Such were my mother's hands.

I remember. . . Many years ago, when I returned from the East, my mother wiped away her tears with her apron and said: "My child, you have returned!" My father gazed at me and also silently wiped away his tears. He did not say anything. He was always silent and watchful. This was his way of rearing. In his view, a man must understand another man even without words. My father, the father who every evening read the Holy Scriptures by the kerosene lantern and explained them to us . . . The lantern is out, the Holy Scriptures book is closed, my father is forever silent. . .

I received all your letters. After this letter I will not write again soon. Only about a half hour is left us between rising and repose. We get enough sleep. We sleep eight hours.

March 26, 1978

This year I did not have the good fortune to take part in the days of assembly—the Palm Sunday ceremonies, the happy Resurrection feast; neither were my eyes gladdened by the Monstrance glittering in the sun's rays, flags fluttering in the spring breeze, the undulating sea of praying souls. But together with you I immersed myself in the solemnity of Lent, with you I walked the Way of the Cross, with you I followed Christ on his way to Jerusalem, spread the palms of my life under His feet, with you I sang "Come, Almighty King," with you escorted Christ to the Repository Altar and thanked Him for remaining in our midst, with you adored Christ's cross and knelt at Christ's grave, singing, "Weep, Angels"; with you, the Christian world, I sang the solemn Gloria and, after receiving Christ into my heart and thanking Him for the determined road of life, I wrote:

"You rose, Christ, on the altars, You rose in my Christian nation, Rise also in my heart!"

April 23, 1978

Today, the believer must suffer many difficult calvaries for his beliefs: he is slowly killed in deadly security police cellars, at terrifying transfer points, stifled in rail car cells, and, in the end,

Ona Pranckūnaitė

he and his love for Christ cooled in the snows of Siberia. And some take fright at this calvary, this slow death. It is very painful when an occasional son of our nation allows himself to be wooed by unscrupulous "fairies" who promise freedom, guarantee life and silver coins. The "freedom" once promised me by the security police does not gladden me. What good is such freedom if I will always be persecuted by an angry, suspicious eye, will be under surveillance everywhere, will always be under scrutiny. Such would be my future freedom. Silver coins . . . What good are they? Today we no longer need the potter's field to bury strangers. Strangers have conquered us and they will bury us where it pleases them.

For us, who have the hope of eternal life, it is not so important under what conditions the days of our life end, where the mounds of our graves will be located. It is important for us that our fellow countrymen, carrying Christ's teachings and light and standing on the mounds of their ancestors, feel nobler, stronger and bolder. For we will be held responsible for not preserving and not handing down the light of the Redeemer's teachings ....

May 1, 1978

. . . In a letter he wrote me, a son of my nation whom I do not know—Aloyzas—included me among the ranks of political prisoners. He is not wrong. Security agents have turned me into one. Though before I did not consider myself a politician and was not involved in politics. As a believer, I was interested in religious literature, I duplicated it, because I understood its usefulness and my Motherland's grave starvation. I also made copies of issues of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, for which I was accused of political activity. I do not and will never consider this publication to be political . . ., because it contains indisputable truth.

The following day my sister sent a telegram about my mother's death. I was not given this telegram. It is as if it never existed. Later, my sister obtained a certificate from the physician, with which she appealed to the Biržai militia chief (where notice had been given of my mother's death), requesting his signature, so that on the strength of this document she could send me a telegram guaranteeing my return. The militia chief refused to sign. He did not confirm that my mother had died. Even though it is common knowledge that without a notice of death a death certificate cannot be issued. I know very well that under the regulations of the Internal Affairs Ministry, a prisoner is released for two weeks from labor camp not only upon the death of the prisoner's parents, but also if the parents' health is in a critical state. But, of course, this does not apply to me ....

I am often searched here. And I alone! During one search, they confiscated my rosary, which I had managed to safeguard for nine months. They also did not return the picture of Christ's Nativity and the wafer. Someone enclosed two Easter pictures in Easter greeting letters. I was not given them. The camp warden sternly asked: "Well, should we again attach these pictures to your personal file?"

Leather factory where O. Pranckūnaitė worked.

"Only to the file! I want my file to be adorned with religious articles!" I would like to ask about the freedom of belief proclaimed by Rev. C.(eslovas) Krivaitis? I suggest that such people follow the example of V. (ladas) Lapienis, whom I met on this painful road. He does not know what lying and hypocricy are. What a perfect man!

Brothers and sisters in Christ, do not fear the crosswinds of this time period! God gives misfortune, He also gives the strength to bear it. The brothers who have sold their conscience for a bowl of soup need to repent, the persecutors need to repent, we also need to repent ourselves.

May 1, 1978

... I spent last spring in the gloomy security police building. There the prisoners' days pass slowly. The city full of hot spring sun, but it never peered through the cellar windows. The cell was cold and damp. Only when we went out into the "pens" to walk around, did we feel the reviving warmth of spring. . . .

May 1978

You are probably wondering what kind of city Kozlovka is. It consists of three villages joined together, spread out over the mountains and their slopes. The area is beautiful: mountains, forests, slopes, and nearby, the Volga, bringing cool breezes. But because the land is foreign, the beauty of the area does not move our hearts. Besides, we see its beauty from one side only, through the half closed second-floor windows of the factory. The houses are wooden, small (like the bathhouses of our country), with one, two, some even three windows with shutters. At the base of the mountains stands the bread-winner of this town—the labor camp. The vegetating creatures of the labor camp are also included among the inhabitants of the town of Kozlovka. I have heard that in the not so distant past these three villages were famous for their numbers of goats.

As we approached the town of Kozlovka by train, we were met by a labor camp vehicle and guards. After another 300 meters we plunged into a fortress of two stone walls and two barbed-wire fences. We walked unabashedly about this fortress because we felt at home ....

This is the special dormatory where, together with criminal prisoners resided Ona Pranckūnaitė.

We were housed on the second floor of a stone building. It is here that our days slip by. They slip by slowly and uniformly. In this labor camp are imprisoned women of various professions and those who once held various positions: engineers, teachers, doctors, bookkeepers, store managers, heads of identification papers offices, students from various institutions, petty thieves, drunks, prostitutes, murderers, black-marketeers and one for the faith, whom you know.

Not so long ago the small Chuvash nation was considered half-wild. Although, of course, even now it is not very far from wild. The people are of medium height, dark-skinned and dark-haired. They wear strange hairy coverings. Many wear on their backs words written in large white letters which we cannot understand. The Chuvash women imprisoned here have nearly all without exception been convicted of murder, for the people of this small nation are very fierce .... Otherwise, all without exception scrupulously keep the laws because their god is the Soviet Union.

Consequently, the labor camp is very strict. Camp living conditions are particularly harsh. Because the camp warden does not have anyone to translate my letters, she has for a long time been sending them to be censored to the Panevėžys militia. At the urging of Vilnius, she has surrounded me with spies. Spies are as plentiful as snakes in the forest! Some of them have visited and know Kaunas well, others visited Vilnius, others still know Moscow well, etc. But Ona has not been anywhere and does not know anything. If the camp warden does not receive any supplementary information, she sometimes runs up to me, places her arms around me and asks a question like, "Tell me, what is your schooling?" "It's in my file!" I reply.

"It's not true!" she shouts back, running from me. I'm truly sorry for those who suffer needlessly. I cannot help.

About myself I can write the following: In this framework, in this atmosphere which shackles me, I feel at peace. Almost normal. I am neither a slave nor a queen, only a person. For myself, I yearn for nothing and choose nothing. I rest like a child in God's protecting arms. I wanted to write you, but did not have an opportunity to do so, that the camp authorities have for a long time been concerned about my health. In January of this year they wanted to send me to the Kemera District, in other words, into exile, but the camp assistant warden objected, stating I would not be able to tolerate the climate and work in that region. Exiles there work on farms and in fields. Presently they are still deliberating what to do with me. You know, the camp authorities try to change the "departure" station for those who are preparing for eternity. Three weeks ago a 22-year old girl died in our camp. They leave . . .

Children of Mary's land, remember us when your weary knees bend at Mary's altar!

May 14, 1978

On May 4th there dawned unexpectedly a morning bringing us freedom. Really! That morning's dawn dispelled the shadows of night from our lives. On May 4th, sixteen of us were paroled from our camp. That day a militia official and the assistant director of the factory which intended to employ us arrived from the city of Ulyanovsk. Kozlovka is about 300 km. (185 miles) from Ulyanovsk. We left Kozlovka about 4:00 P.M. and arrived in Ulyanovsk at about 9:00 A.M. the following day. We were tired and cold from the trip. Despite the cold, by morning we had nonetheless plunged into the realm of dreams. When we opened our sleepy eyes, a sun-dappled forest beckoned us at a distance. After passing the forest, we saw the factory chimneys of Ulyanovsk. We were housed in a two story dormitory. The room is clean, about 18 sq. m. (190 sq. ft.) in size. With me live three women who have murdered their husbands. The room's two windows are decorated with bars. When we were given physicals, the doctors expressed doubts about my health. The management of the leather tanning factory had already assigned us work, but the doctors would not consent to the work assigned me without any steady work for two days, sending me from one job to another and felling me to choose my own work. I did not choose. There was nothing to choose. The smell of emulsifiers and dyes, and the heat is pervasive. They assigned a job at their own discretion. The first days were hard. The work does not seeem too bad.

Four militiamen live in our dormitory with their families. They take turns standing guard day and night. There is an inspection at 10:00 P.M. We must also register every Sunday at this dormitory. Before work, after work and on Sundays we can freely walk around the city, go to the mountains and for a swim in the Volga, etc. But we must return to the dormitory by 10:00 P.M. It is much better here than in the labor camp. Though the first months were hard. We have started our lives from scratch with needle, match and spoon ....

June 4, 1978

We are allowed to receive an unlimited number of letters, packages and money orders and everything they contain. No one checks anything here and there are no restrictions. Do not send anything, because I want to accept the present moment as God ordained it from eternity. For it is beneficial for a person to experience the taste of cold and hunger and other privations.

Today is Sunday. I went to the small Orthodox church to offer up the cherry blossom you sent. As you know, Orthodox churches do not have altars on which flowers may be offered. I approached almost stealthily the painting of the Crucified Christ which depicts the Blessed Virgin Mary lost in sorrow on one side, and St. John on the other, and secretly offered up as a gift to Mary from all the children of her beloved land a blossom from my Motherland's orchards.

. . . When you write a letter, please enclose a large needle. There are none in Ulyanovsk.. .If we work twenty days per month we are paid sixty rubles. In this place, one can only feed oneself for that much money. This city has no butter, meat or sausages at all; bacon is sold in special stores. It costs 5.47 rubles per kg. (2.2 lbs.). We do not buy meat products and do not worry about them. We eat milk, bread and potatoes. Milk is like whitened water: after a bottle of milk is consumed, there is no need to wash the bottle, it is clean ... In packages could you please include, of course, if they are available in the stores, the following food products: a few kilograms of fruit gelatin and some cheap coffee or cocoa. These food products are unavailable in Ulyanovsk. . .

My dear, please don't be upset over the fact that your mail box is broken into and my letters read .... I know very well that those who are interested in my letters are security agents and I hide nothing from them.

... I went to this city's sole small Orthodox church . . . When I left, I could not stop being amazed at the size of the crowd. I am astonished that, though God's name has for so long been and still is being erased from the hearts of this nations's people, it cannot be completely erased. I once visited the dormitory supervisor. In his nicely furnished apartment my astonished eyes saw religious pictures hanging in places of honor. My heart was glad ....

July 3, 1978

I still do the same work, i.e., tan leather. When I glance at those million-ruble hills of hides, a baffling question forces itself into my mind: into what country did the live-stock flee after shedding its hide?

Or perhaps it is now fashionable to walk around with no hide? If they had been slaughtered, there would be meat in the stores. The stores are empty: there are no heads, no hooves, no tails. There really are none!

. . . My nation, walk with a firm step on the paths consecrated by the blood and sweat of heroes and feel your hand in the Lord's palm. In the nation's churches, remember us and all who are suffering misfortune!

Ona Pranskūnaitė

Vladas Lapienis writes

(...) Of course, it would be more pleasant for you if I told only of good news from the labor camp. But why deceive myself and others? Reality intrudes on its own (...). Due to negligence, I received Tiesa (Truth) only beginning August 2nd, but still do not get the magazine Nauka i iizn (Science and Life) and the newspaper Neuer Leben (New Life). I do not know where two months worth of Kom-jaunimo tiesa (Truth of the Communist Youth)disappeared, as well as certain other newspapers and magazines.

The authorities of the third colony know quite well where I am because several of the letters you sent to Barashev were forwarded to me here at Camp 19. However, other letters from you as well as other people, sent to the old address, were returned to the senders, more than a thousand kilometers away, instead of being forwarded to the neighboring 19th camp . . .

September 10, 1978 Vladas Lapienis

Petras Paulaitis writes

May 19, 1978

... I remember and carry in my heart nearly all the people with whom I suffered common misfortunes during 1958-1961. Only God knows how many of them still remember me. But that is not so important. What is important is that they be good persons and live good, happy lives. From January 30, 1961 to April 1, 1974 I lived in the "zebra" kingdom. I do not know whether because of my weaker health (my legs began to swell in the damp and cramped ce 11 s) I was tran sfe rre d to a 1 e s s s tri ct re gime camp. From the re to anothe r, and again to another, but always to where there were fewer people and less living space. And the benefit is merely that we are in unlocked cells, with barless windows and have a different uniform

—one without stripes. In other words—nothing good. One can feel everywhere the trend toward worse conditions. But so far we get enough of that daily bread. And there were days when we feasted on bread only in our dreams. You ask if you can send money and whether one can buy anything. Money can be sent, but we don't see it and can spend no more than 7-9 rubles per month in the camp store. And those who have transgressed against the authorities in some way or have not filled their work quotas are deprived partially or completely of the right to use the store.

Everyone is forced to work. The infirm are assigned a special number of hours they can work. For instance, I am assigned to work six hours, but in fact I work much longer. Of course, the work is not in the fields or forests, but there is enough strain. The most important thing is that you keep constantly busy. So I still earn enough money to buy things. It is difficult to say how this work and pay will go in the future, because I've already been pulling the yoke under Russia's domination since April 12, 1947 with no vacation, with no "repairs", with no quiet moment. And furthermore what food do we get for this work? What maintenance?

Moses directed the Jews not to muzzle working oxen (for the hungry animals picked up in passing mouthfuls of hay or a corn cob). But here the disseminators of a new civilization and humani-tarianism are doing the complete opposite: they promulgate all kinds of "new constitutions," and they supplement them with secret instructions, not publicized anywhere except in the corridors of our barracks which muzzle us so we will stay hungry, will not talk, will not moan. But people who are split up, divided, scattered into small groups and shut in inaccessible "wells," suffer and remain silent. I am silent also, but I believe in Divine Providence. Without It not a single hair falls to the ground. And "fiat voluntas Tua!" (Your will be done!) "Good comes from every evil." Freedom is precious.

No parcels of books, magazines or newspapers are allowed. Nothing can be sent or received, except two 1-kg (2.2 lbs) parcels and one 1.5-kg (3.3 lbs) package per year. Newspapers and magazines can be subscribed with one's own money through the camp administration. But the press we subscribe to quite often disappears, and is nearly always late. It is frightening: we haven't seen a good book for a long time now—they give us neither printed nor written language. "Let Lithuania (the prisoners)," they say, "be ignorant and dark (backward and downtrodden)".

Living conditions are also very poor. It is impossible to list all the hardships and shortages. Medical care is poor, the pharmacy has almost nothing for us. I have long been bothered by corns on my feet. It is "sweet" to remember shoes, but there is nothing here to heal them with . . .

But I have no wife or mother. It is fortunate that the world is not without good people. Each in his own way, through the support and prayer of good people, I am into the 31st year of my sentence. And only four and a half years remain. On October 20, 1982 I will complete giving the conqueror the terrible tribute of the innocent.

But I must finish. Because the fences of our "well" are high, the letter may not be able to climb them. (He asks for plasters to heal his corns, envelopes, cookies, fudge candy, postal stamps . . .).

Please believe that I write all this and blush like a lobster. . . Above all I ask that you remember me in your prayers at the Lord's altar.

Please convey my greetings to our common friends when you see them.

Petras Paulaitis